Motivation

Modern CPUs have multiple cores that can be used to concurrently run executions.

If we were to build an application using multiple processes that take advantage of multiple cores, each process would need its own virtual memory. If, say, we wanted to perform computations on each element in a large array, having a virtual memory for each computation would create a large overhead.

To mitigate this, we use threads, which can perform divided tasks with a shared address space.

| Process | Thread |

|---|---|

| Process ID | Thread ID |

| Address space: Code, data, heap, stack | Set of registers, including PC and SP |

| Open file descriptors | Stack for local vars and return address |

| Current working directory | |

| User and group ID |

why the stack only?

the stack stores function calls and return addresses, local variables, parameter passing, and control flow. these are all needed for a thread to be unique from one another.

Thread API

Note:

pthreadis short for POSIX thread.- mutex is short for “mutual exclusion”, a principle that ensures only one thread can access a particular resource or piece of code at a time

Thread Creation and Completion

#include <pthread.h>

int

pthread_create(pthread_t *thread, // structure used to interact with this thread

const pthread_attr_t *attr, // specify attributes this thread has

void *(*start_routine)(void*), // which function thread should run

void *arg // argument to be passsed to functionBreaking down the third argument:

(start_routine): the name of function thread should run(*start_routine)(void*): pass in a single argument of typevoid*as argument tostart_routinevoid *: return a void pointer

Example:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

typedef struct {

int a;

int b;

} myarg_t;

typedef struct {

int x;

int y;

} myret_t;

void *mythread(void *arg) {

// return value must be in heap

myret_t *rvals = malloc(sizeof(myret_t));

rval->x = 1;

rvals->y = 2;

return (void *) rvals;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

pthread_t p;

myret_t *rvals;

myarg_t args = { 10, 20 };

pthread_create(&p, NULL, mythread, &args);

pthread_join(p, (void **) &rvals);

// name of thread^ ^pointer to retrieve return value from thread p

printf("returned %d %d\n", rvals->x, rvals->y);

free(rvals)

return 0;

...

}Locks

// two ways to initialize lock:

// static method:

pthread_mutex_t lock = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

// dynamic method:

pthread_mutex_t lock;

int rc = pthread_mutex_init(&lock, NULL);

assert(rc == 0); // always check success!

pthread_mutex_lock(&lock);

x = x + 1; // Protect critical section

pthread_mutex_unlock(&lock);

// if we used dynamic method, we must destroy the lock:

pthread_mutex_destroy();If no other thread holds the lock when pthread_mutex_lock() is called, the thread will acquire the lock and enter the critical session. If another thread does hold the lock, the thread will not return from the call until it has acquired the lock.

More pthread routines:

pthread_mutex_trylock()returns failure if the lock is already heldpthread_mutex_timedlock()returns after timeout or after acquiring the lock

Condition Variables

Condition variables allow threads to suspend execution and relinquish the processor until some condition is met, at which point a thread is awakened to resume execution.

Workflow:

- Lock a mutex

- Perform a while-loop check on a condition. If the condition is not met, wait on the condition variable, effectively putting the thread to sleep until the condition changes.

- Once awakened and condition is met, proceed with critical section of code that required the condition

- Unlock mutex

Using pthread_cond_wait():

pthread_mutex_t lock = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

pthread_cond_t cond = PTHREAD_COND_INITIALIZER;

Pthread_mutex_lock(&lock);

while (ready == 0)

Pthread_cond_wait(&cond, &lock); // needs lock as param because it needs

// to unlock for the ready signal to lock

Pthread_mutex_unlock(&lock);Code to wake waiting thread:

Pthread_mutex_lock(&lock);

ready = 1;

Pthread_cond_signal(&cond);

Pthread_mutex_unlock(&lock);Compiling and Running

We must add a new flag:

prompt> gcc -o main main.c -Wall -pthread

Synchronization Primitives

Since a simple line of code can turn into three instructions that could run non-deterministically in multiple threads, we want to ensure that instructions run as uninterruptable groups, or atomic groups.

We use synchronization primitives to create atomicity for critical sections.

Locks

As mentioned under Thread API, we use a lock in the following manner:

lock_t mutex; // some globally-allocated lock 'mutex'

...

lock(&mutex);

balance = balance + 1; // critical section

unlock(&mutex);To design this lock, we must accomplish the following goals:

- mutual exclusion: lock must prevent multiple threads from entering a critical section

- fairness: each thread contending for the lock must get a fair shot at acquiring it

- performance: time overheads added to use the lock must be reasonable

- What is the overhead of grabbing and releasing a lock?

- With multiple threads, are there performance concerns?

- With multiple CPUs, are there performance concerns?

Evaluating Spin Locks

- Correctness: spin locks provide mutual exclusion.

- Fairness: spin locks don’t provide any fairness guarantees.

- Performance:

- single CPU: before giving up the CPU, threads will spin for the duration of a time slice

- multiple CPU: spinning will be done in one thread at the same time another thread completes critical section

Failed Attempts: Controlling Interrupts

void lock() {

DisableInterrupts();

}

void unlock() {

EnableInterrupts();

}Negatives:

- Malicious program could call

lock()and go in an infinite loop, disabling interrupts forever. (Never trust processes that can perform privileged operations!) - If there are multiple processors, thread will just execute in a processor that does not have interrupts disabled.

- We don’t want interrupts to be lost, i.e., a CPU missing that a disk has finished a read request.

This method is still used by the OS, since trust issues disappear in this context.

Failed Attempts: Loads/Stores

typedef struct __lock_t { int flag; } lock_t;

void init(lock_t *mutex) {

// 0 -> lock is available, 1 -> held

mutex->flag = 0;

}

void lock(lock_t *mutex) {

while (mutex->flag == 1) // wait until lock is available

; // spin-wait

mutex->flag = 1; // hold lock

}

void unlock(lock_t *mutex) {

mutex->flag = 0;

}Negative:

- Correctness: if two threads detect an available lock at a similar time, the spin-wait could cause both of them to set the flag to 1.

- Performance; spin-waiting is costly

Spin Locks with Test-And-Set

int TestAndSet(int *old_ptr, int new) {

int old = *old_ptr; // fetch old value at old_ptr

*old_ptr = new; // store 'new' into old_ptr

return old; // return the old value

}

...

typedef struct __lock_t {

int flag;

} lock_t;

void init(lock_t *lock) {

// 0: lock is available, 1: lock is held

lock -> flag = 0;

}

void lock(lock_t *lock) {

while (TestAndSet(&lock->flag, 1) == 1) // only exits when TestAndSet returns 0

; // spin-wait (do nothing)

}

void unlock(lock_t *lock) {

lock->flag = 0;

}Positive: TestAndSet tests the value of the flag AND sets the lock to 1 atomically at the same time.

Given a single CPU, spin-locking requires a preemptive scheduler, which will interrupt a thread via a timer.

Can't the operation of

TestAndSetbe hijacked as well?Modern processors provide special instructions designed to perform certain operations, like

TestAndSet, atomically.

Compare-And-Swap

int CompareAndSwap(int *ptr, int expected, int new) {

int original = *ptr;

if (original == expected)

*ptr = new;

return original;

}

...

void lock(lock_t *lock) {

while (CompareAndSwap(&lock->flag, 0, 1) == 1)

; // spin

}While Test-And-Set would unconditionally set the pointer value, Compare-And-Swap adds an additional check with a new expected parameter.

This reduces unnecessary updates, where the value is set regardless of its current state.

Load-Linked and Store-Conditional

int LoadLinked(int *ptr) {

return *ptr;

}

int StoreConditional(int *ptr, int value) {

if (no update to *ptr since LoadLinked to this address) {

*ptr = value;

return 1; // success!

} else {

return 0; // failed to update

}

}

void lock(lock_t *lock) {

while (1) {

while (LoadLinked(&lock->flag) == 1)

; // spin until it's zero

if (StoreConditional(&lock->flag, 1) == 1)

return; // if set-it-to-1 was a success

// otherwise: try it all over again

}

}Load-linked: atomizes the pointer return for the while loop check

Store-conditional: attempts to write a value to the memory location if no updates have occurred to that location since the preceding load-linked operation

What problem are we addressing here?

While we go from checking that the lock is free to locking it for this thread, we need to ensure that the lock hasn’t been locked by some other thread in the meantime.

Ticket Lock

Now we address the fairness problem…

int FetchAndAdd(int *ptr) {

int old = *ptr;

*ptr = old + 1;

return old;

}

...

typedef struct __lock_t {

int ticket;

int turn;

} lock_t;

void lock_init(lock_t *lock) {

lock->ticket = 0;

lock->turn = 0;

}

void lock(lock_t *lock) {

int myturn = FetchAndAdd(&lock->ticket); // take-a-number system

while (lock->turn != myturn) // each unlock increases turn

; //spin

}

void unlock(lock_t *lock) {

lock->turn = lock->turn + 1;

}- Fetching and incrementing: upon attempting to acquire the lock, each thread calls

FetchAndAddto receive a unique ticket number and increment theticketcounter - Waiting for turn: the thread then enters a spin-wait loop until its ticket number matches the

turnvalue - Incrementing turn: once a thread finishes its critical section work, it calls

unlock, which increments theturnvalue, allowing the next thread in line to enter the critical section.

Fundamental Issue with Spinning

.jpeg)

When thread 2 gets a share of running time, it does not get to perform any meaningful tasks if it is waiting for another thread to give up a lock that won’t be given up.

Solution: Just Yield

void lock() {

while (TestAndSet(&flag, 1) == 1)

yield(); // don't spin forever, just yield instead

}

void unlock() {

flag = 0;

}This works for two threads, but with 100 threads, we will still be waiting for 99 of them to yield per instruction.

Solution: Queues

int TestAndSet(int *old_ptr, int new) {

int old = *old_ptr; // fetch old value at old_ptr

*old_ptr = new; // store 'new' into old_ptr

return old; // return the old value

}

...

typedef struct __lock_t {

int flag;

int guard;

queue_t *q;

} lock_t;

void lock_init(lock_t *m) {

m->flag = 0;

m->guard = 0;

queue_init(m->q);

}

void lock(lock_t *m) {

while (TestAndSet(&m->guard, 1) == 1)

; // acquire guard lock by spinning

if (m->flag == 0) {

m->flag = 1; // lock is acquired

m->guard = 0;

} else { // still locked

queue_add(m->q, gettid());

m->guard = 0;

park();

}

}

void unlock(lock_t *m) {

while (TestAndSet(&m->guard, 1) == 1)

; // acquire guard lock by spinning

if (queue_empty(m->q))

m->flag = 0; // let go of lock; no one wants it

else

unpark(queue_remove(m->q)); // hold lock (for next thread)

m->guard = 0;

}- Guard Lock:

guardvariable ensures atomic access to the lock structure itself. this prevents race conditions when threads modify the queue or check theflagstate. - Queue Management: threads that attempt to acquire the lock but find it already held (

flag == 1) are added to a queue (queue_add(m->q, gettid());) instead of continuously spinning. - Conditional Blocking (

park()): instead of actively spinning, threads that cannot acquire the lock are put to sleep (park()), actively being descheduled by the operating system. This operation conserves CPU resources by halting the execution of threads that would otherwise be spinning idly, waiting for the lock to become available. - Wake-up of Waiting Threads (

unpark()): Upon releasing the lock, the unlocking thread checks the queue; if there are waiting threads (!queue_empty(m->q)), it wakes up the next thread (unpark(queue_remove(m->q))). This ensures that threads are reactivated in the order they attempted to acquire the lock, maintaining the fairness established by the queue.

The point is that the thread sleeps when it isn’t its turn.

Locked Data Structures

Approximate Counters

typedef struct __counter_t {

int global; // global count

pthread_mutex_t glock; // global lock

int local[NUMCPUS]; // local count (per CPU)

pthread_mutex_t llock[NUMCPUS]; // local locks

int threshold; // update freq.

}

void init(counter_t *c, int threshold) {

c->threshold = threshold;

c->global = 0;

pthread_mutex_init(&c->glock, NULL);

int i;

for (i = 0; i < NUMCPUS; i++) {

c->local[i] = 0;

pthread_mutex_init(&c->llock[i], NULL);

}

}

void update(counter_t *c, int threadID, int amt) {

int cpu = threadID % NUMCPUS; // identify what thread we are working with

pthread_mutex_lock(&c->llock[cpu]); // lock local thread

c->local[cpu] += amt; // counter

if (c->local[cpu] >= c->threshold) { // threshold check

pthread_mutex_lock(&c->glock);

c->global += c->local[cpu];

pthread_mutex_unlock(&c->glock);

c->local[cpu] = 0;

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&c->llock[cpu]);

}

int get(counter_t *c) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&c->glock);

int val = c->global;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&c->glock);

return val; // this will be an approximate count!

}__counter_tglobalcounter protected byglockrepresents aggregated count across all threads- array of local counters

local[NUMCPUS]protected byllock[NUMCPUS], each associated with a CPU, tracks counts locally thresholdindicates frequency at which local count is transferred to the global count

update()- determine relevant CPU based on threadID

- local lock is acquired, local counter is incremented

- when local counter exceeds threshold, thread acquires global lock, transfers local count to global counter, and resets local counter.

get()- fetch approximate global count, which is an approximate.

Linked Lists

typedef struct __node_t {

int key;

struct __node_t *next;

} node_t;

typedef struct __list_t {

node_t *head;

pthread_mutex_t lock;

} list_t;

void List_Init(list_t *L) {

L->head = NULL;

pthread_mutex_init(&L->lock, NULL);

}

int List_Insert(list_t *L, int key) {

node_t *new = malloc(sizeof(node_t));

if (new == NULL) { // dealing with malloc error

perror("malloc");

return -1; // fail

}

new->key = key;

pthread_mutex_lock(&L->lock); // just lock critical section

new->next = L->head; // add new as head of L

L->head = new;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&L->lock);

return 0; // success!

}

int List_Lookup(list_t *L, int key) {

int rv = -1;

pthread_mutex_lock(&L->lock);

note_t *curr = L->head;

while (curr) {

if (curr->key == key) {

rv = 0;

break;

}

curr = curr->next;

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&L->lock);

return rv; // fail if not found, success if found

}__node_t- individual elements of the linked list, containing data (

key) and pointer to the next node (next)

- individual elements of the linked list, containing data (

__list_t- represents linked list itself, containing pointer to the head node (

head) and a mutex (lock) - mutex prevents concurrent modifications of the list

- represents linked list itself, containing pointer to the head node (

List_Insert(list_t *L, int key)- dynamically allocate memory for a new node and assign it to the given key

- acquire mutex lock to enter critical section, ensuring exclusive access to the list

- insert the new node at the beginning of the list, making it the new head

- release mutex

List_Lookup(list_t *L, int key)- acquire mutex lock

- traverse the list and search for a node with the specified key

- release the mutex lock after search is completed

Queues

typedef struct __node_t {

int value;

struct __node_t *next;

} node_t;

typedef struct __queue_t {

node_t *head;

node_t *tail; // for queue and dequeue, need access to both head and tail

pthread_mutex_t head_lock, tail_lock;

} queue_t;

void Queue_Init(queue_t *q) {

node_t *tmp = malloc(sizeof(node_t));

tmp->next = NULL;

q->head = q->tail = tmp;

pthread_mutex_init(&q->head_lock, NULL);

pthread_mutex_init(&q->tail_lock, NULL);

}

void Queue_Enqueue(queue_t *q, int value) {

node_t *tmp = malloc(sizeof(node_t));

assert(tmp != NULL); // malloc check

tmp->value = value;

tmp->next = NULL;

pthread_mutex_lock(&q->tail_lock); // only for critical section

q->tail->next = tmp;

q->tail = tmp;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&q->tail_lock);

}

int Queue_Dequeue(queue_t *q, int *value) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&q->head_lock);

node_t *tmp = q->head;

node_t *new_head = tmp->next;

if (new_head = NULL) {

pthread_mutex_unlock(&q->head_lock);

return -1; // queue was empty

}

*value = new_head->value; // pop from head

q->head = new_head;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&q->head_lock);

free(tmp);

return 0;

}__node_t- represents item in the queue, with

valueand a pointer to the next node (next)

- represents item in the queue, with

__queue_t- represents queue itself, has pointers to head and tail nodes

- includes separate locks for the head and tail to ensure concurrent access

Queue_Init()- dummy node is allocated and initialized, ensures that the list is never empty

- both head and tail pointers of the queue are set to dummy node, indicating an initially empty queue

- head and tail locks are initialized, preparing queue for concurrent access

Queue_Enqueue()- new node is allocated and its value is set to

value - the tail lock is acquired to ensure exclusive access to the tail of the queue

- new node is inserted at the tail, and tail pointer is updated to this new node

- tail lock is released

- new node is allocated and its value is set to

Queue_Dequeue()- head lock is acquired to ensure exclusive access to the head of the queue

- method checks if queue is empty

- if empty, release lock and return error

- if not empty, value of next node is retrieved, and the head pointer is updated to point to the next node

- the head lock is released, and the actual value node after the head node that has been dequeued is freed

A note on dummy nodes

Remember,

headwill be the dummy node, andhead->nextwill be the first actual value node. We do free the sentinel node inQueue_Dequeue(), but even thoughnew_headcontains some value, it will never be used and therefore becomes conceptually a sentinel node.

Concurrent Hash Table

What is a bucket?

A bucket is a fundamental storage unit of a hash map that holds entries (key-value pairs)

note: refer back to ^b55abe for LinkedList-related function calls

#define BUCKETS (101)

typedef struct __hash_t {

list_t lists[BUCKETS];

} hash_t;

typedef struct __list_t {

node_t *head;

pthread_mutex_t lock;

} list_t;

void Hash_Init(hash_t *H) {

int i;

for (i = 0; i < BUCKETS; i++)

List_Init(&H->lists[i]);

}

int Hash_Insert(hash_t *H, int key) {

// [key % BUCKETS] calculates index for a hash table bucket

return List_Insert(&H->lists[key % BUCKETS], key);

}

int Hash_Lookup(hash_t *H, int key) {

return List_Lookup(&H->lists[key % BUCKETS], key);

}__hash_t- consists of an array of

list_tstructureslists[BUCKETS], where eachlist_tis a linked list that acts as a bucket.

- consists of an array of

Hash_Init()- Iterates through each bucket in the hash table

- Initializes each linked list (bucket) by calling

List_Init(), setting up the mutex lock and initializing the head pointer toNULL

Hash_Insert()- The hash function determines the appropriate bucket for the key

List_Insertis called on the corresponding bucket’s linked list to add the key

Hash_Lookup()- Hash function determines which bucket may contain the key

List_Lookupis called on the bucket’s linked list to search for the key

Basically works just like a hash map, but uses a thread-safe implementation of Linked List.

Condition Variables

If a parent thread wants a child thread to finish before proceeding, it might want to wait for some condition to become true.

Definition and Routines

int done = 0;

pthread_mutex_t m = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

pthread_cond_t c = PTHREAD_COND_INITIALIZER; // condition variable

void thr_exit() {

Pthread_mutex_lock(&m);

done = 1;

Pthread_cond_signal(&c); // signals that we are done here

Pthread_mutex_unlock(&m);

}

void *child(void *arg) {

printf("child\n");

thr_exit();

return NULL;

}

void thr_join() {

Pthread_mutex_lock(&m);

while (done == 0)

Pthread_cond_wait(&c, &m); // wait for condition

Pthread_mutex_unlock(&m);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("parent: begin\n");

pthread_t p;

Pthread_create(&p, NULL, child, NULL); // no attributes and arguments

thr_join();

printf("parent: end\n");

return 0;

}- Initialization: a global variable

doneis initialized to 0, a mutexmis created and initialized, and a condition variablecis also initialized. these are used to synchronize the parent and child threads. - Child Thread (

childfunction): when the child thread is created, it prints “child”, callsthr_exit()to indicate the work is done, and exits.- within

thr_exit(), the mutexmis locked,doneis set to1, andpthread_cond_signal()wakes up the parent thread waiting on the condition variablec. then, mutex is unlocked.

- within

- Parent Thread (

thr_joinfunction): parent thread callsthr_join()to wait for the child thread to complete.- It locks mutex

m, and checks thedonevariable.- If still

0, the parent thread callspthread_cond_wait(), which atomically unlocks the mutex and suspends the execution of the calling thread until the condition variablecis signaled. - Once signaled,

pthread_cond_wait()automatically re-acquires the mutexmand the function returns, allowing the parent thread to proceed and unlock the mutex.

- If still

- It locks mutex

- Completion: after

thr_join()returns, the parent thread knows the child has finished.

Some tips:

- Always hold the lock when calling signal

- Always hold the lock when waiting

The Producer/Consumer (bounded buffer) Problem

Producers generate data items and place them in a buffer, consumers grab said items from the buffer and consume them in some way.

Problem: ensure that producers do not add data to the buffer when it is full (to prevent overwriting), and that consumers do not attempt to remove data from the buffer when empty.

To synchronize:

- Mutual exclusion: only one thread (either a producer or consumer) can modify (produce or consume) the buffer at any given time to prevent data corruption.

- Condition synchronization: producers and consumers must wait (block) under certain conditions (buffer full for producers, buffer empty for consumers), and be notified when those conditions change.

Put and Get Routines:

int buffer[MAX];

int fill_ptr = 0;

int use_ptr = 0;

int count = 0;

void put(int value) {

buffer[fill_ptr] = value;

fill_ptr = (fill_ptr + 1) % MAX;

count++;

}

int get() {

int tmp = buffer[use_ptr];

use_ptr = (use_ptr + 1) % MAX;

count--;

return tmp;

}Producer and Consumer Routines:

cond_t empty, fill;

mutex_t mutex;

void *producer(void *arg) {

int i;

for (i = 0; i < loops; i++) {

Pthread_mutex_lock(&mutex);

while (count == MAX)

Pthread_cond_wait(&empty, &mutex);

put(i);

Pthread_cond_signal(&fill);

Pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutex);

}

}

void *consumer(void *arg) {

int i;

for (i = 0; i < loops; i++) {

Pthread_mutex_lock(&mutex);

while (count == 0)

Pthread_cond_wait(&fill, &mutex);

int tmp = get();

Pthread_cond_signal(&empty);

Pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutex);

printf("%d\n", tmp);

}

}- a producer only sleeps if all buffers are currently filled.

- a consumer only sleeps if all buffers are currently empty.

Potential mistakes mentioned in textbook:

if (count == 0)vs.while (count == 0)- Since the wait does not return back to a check in an if statement, a consumer thread can be mistaken about whether there was a change in the condition.

- A while loop solves this by forcing every wake to do a condition check first.

- one condition vs. two conditions

- two consumers run first, and both go to sleep.

- then producer runs, adds data, and wakes the first consumer up.

- the producer then loops back, realizes buffer is full, and waits.

- now, the first consumer is ready to run, and the second consumer thread and the producer thread are both sleeping.

- the first consumer wakes by returning from wait, rechecks the condition, and finding the buffer full, consumes the value.

- the first consumer then signals on the condition to wake up a thread

- if it wakes up producer, great!

- but if it wakes up the second consumer, it too will sleep, and now we have three sleeping threads.

- so we need two conditions to keep track of both the filling of the buffer, and the emptying of the buffer.

Covering Conditions

Say two allocate threads waiting for a heap have >0 bytes free, $T_{a} =$ allocate(100) and $T_{b} =$ allocate(10)

A third thread calls free(50), but makes no guarantee if it will signal $T_{a}$ or $T_{b}$.

To mitigate this problem, we replace a signal to pthread_cond_broadcast(), which wakes up all waiting threads. These threads then may be assessed with a thread scheduling algorithm, which may intelligent pick the allocation that is possible.

But waking up multiple threads creates an overhead, increasing CPU usage.

Semaphores

semaphore: object with an integer value that we can manipulate with two routines: sem_wait(), and sem_post().

#include <semaphore.h>

sem_t s;

sem_init(&s, 0, 1);- Breaking down

sem_init(*s, 0, 1);:0indicates that the semaphore is shared between threads in the same process1indicates that the semaphoreswill be initialized to the value1

// either returns right away (s >= 1), or suspend execution and wait

int sem_wait(sem_t *s) {

decrement the value of semaphore s by one

wait if value of semaphore s is negative

}

// simply increments s, and wakes up one of any waiting thread(s)

int sem_post(sem_t *s) {

increment the value of semaphore s by one

if there are one or more threads waiting, wake one

}The value of the semaphore, when negative, is equal to the number of waiting threads.

Binary Semaphore (Lock)

sem_t m;

sem_init(*m, 0, 1); // init to 1 to make all other threads wait before m finishes

sem_wait(*m);

// critical section here

sem_post(*m);Semaphores for Ordering

Semaphores can also be used to order events in a concurrent program. The pattern here is one thread waiting for something to happen, and another thread making that something happen.

sem_t s;

void *child(void *arg) {

printf("child\n");

sem_post(&s); // signal here: child is done

return NULL;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

sem_init(&s, 0, 0);

printf("parent: begin\n");

pthread_t c;

Pthread_create(*c, NULL, child, NULL);

sem_wait(*s); // wait here for child

printf("parent: end\n");

return 0;

}The Producer/Consumer (Bounded Buffer) Problem, again!

void *producer(void *arg) {

int i;

for (i = 0; i < loops; i++) {

sem_wait(&empty);

sem_wait(&mutex); // lock is held here and not line above

// this ensures that thread isn't locked before we

// exit wait()

put(i);

sem_post(&mutex);

sem_post(&full);

}

}

void *consumer(void *arg) {

int i;

for (i = 0; i < loops; i++) {

sem_wait(&full);

sem_wait(&mutex);

int tmp = get();

sem_post(&mutex);

sem_post(&empty);

printf("%d\n", tmp);

}

}Reader-Writer Locks

Locks aren’t necessary in reading (lookup) tasks, as long as there is not a writing (insert) tasks currently ongoing.

typedef struct _rwlock_t {

sem_t lock; // binary semaphore for a basic lock

sem_t writelock; // allow ONE writer/MANY readers

int readers; // number of readers in a critical section

}

void rwlock_init(rwlock_t *rw) {

rw->readers = 0;

sem_init(&rw->lock, 0, 1);

sem_init(&rw->writelock, 0, 1);

}

void rwlock_acquire_readlock(rwlock_t *rw) {

sem_wait(&rw->lock);

rw->readers++;

if (rw->readers == 1) // first reader gets writelock

sem_wait(&rw->writelock);

sem_post(&rw->lock);

}

void rwlock_release_readlock(rwlock_t *rw) {

sem_wait(&rw->lock);

rw->readers--;

if (rw->readers == 0) // last reader lets it go

sem_post(&rw->writelock);

sem_post(&rw->lock);

}

void rwlock_acquire_writelock(rwlock_t *rw) {

sem_wait(&rw->writelock);

}

void rwlock_release_writelock(rwlock_t *rw) {

sem_post(&rw->writelock);

}- struct

_rwlock_tlock: a binary semaphore acting as a basic lock to protect access to thereaderscounterwritelock: a binary semaphore to ensure that when a writer is active, no readers can access the resourcereaders: a counter tracking the number of readers currently in the critical section

rwlock_init()- Initializes lock by setting

readersto 0 and both semaphores to 1, indicating that both locks are available.

- Initializes lock by setting

- Acquire read lock:

rwlock_acquire_readlock()- Lock acquisition: reader acquires the

locksemaphore to safely incrementreaderscount - First reader actions: if this is the first reader, it also waits on the

writelocksemaphore. This step ensures that if a writer is active or waiting, the reader will block until the writer is finished. - Release lock: finally, the reader releases the

locksemaphore, allowing other readers or writers to modify thereaderscount.

- Lock acquisition: reader acquires the

- Release read lock:

rwlock_release_readlock()- Lock acquisition: the reader acquires the

locksemaphore to safely decrement thereaderscount - Last reader actions: if this is the last reader, it posts the

writelocksemaphore, indicating that writers can now acquire a writelock if they were blocked. - Release lock: the semaphore

lockis released

- Lock acquisition: the reader acquires the

- Acquire write lock:

rwlock_acquire_writelock()- A writer waits for the

writelocksemaphore. - This operation blocks if any readers are currently reading or if another writer holds the lock, ensuring exclusive access.

- A writer waits for the

- Release write lock:

rwlock_release_writelock()- The writer releases the

writelocksemaphore, allowing other waiting writers or readers to proceed.

- The writer releases the

- Important Characteristics

- Reader Preference: preference is given to readers, where once a reader has a

writelock, additional readers can enter critical section without waiting, but writers can’t until the last reader exits. - Mutual Exclusion: ensured for writers by

writelock, no two writers can enter the critical section simultaenously.

- Reader Preference: preference is given to readers, where once a reader has a

Note, they add more overhead and do not end up speeding up performance compared to just using simple and fast locking primitives.

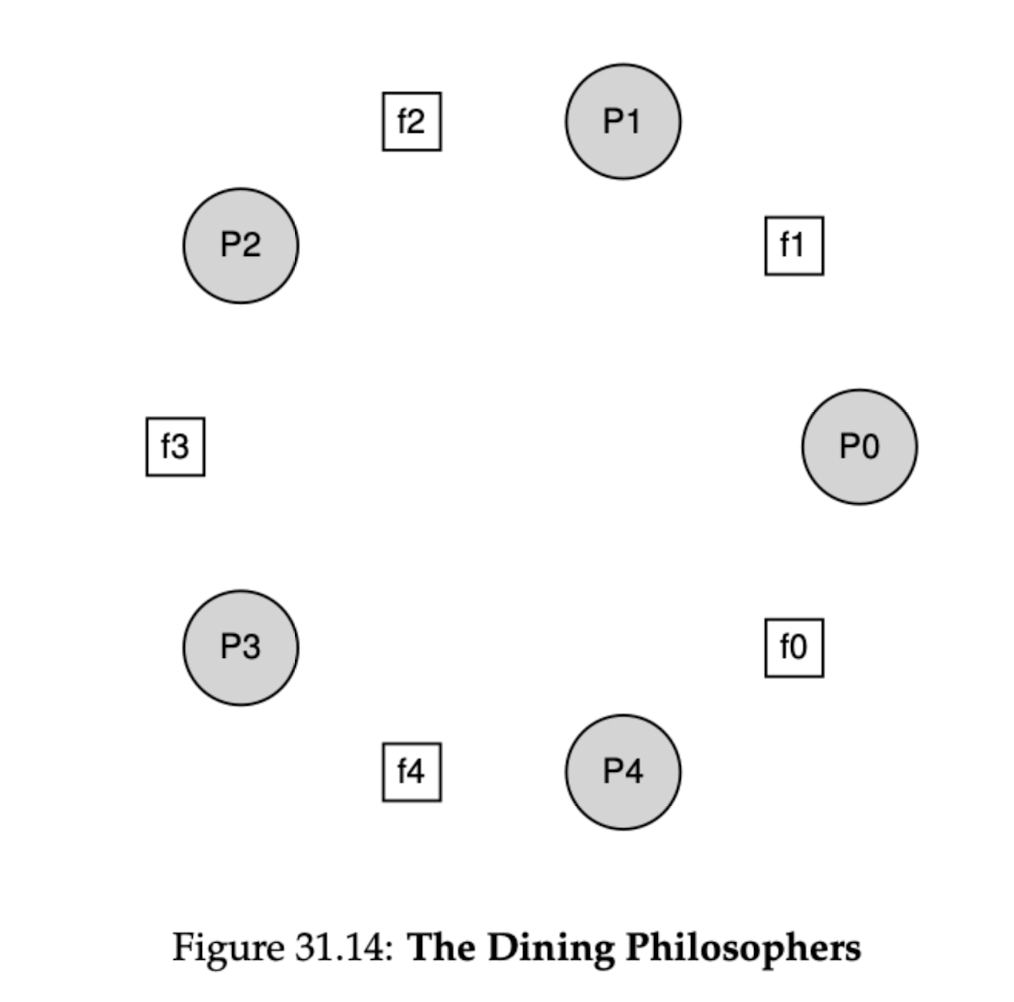

The Dining Philosophers

A philosopher needs two forks to eat. They alternate between eating and talking.

The gist: you get high concurrency (as many philosophers get to eat at the same time) and no starvation by having a lock for each fork, and having just one of the philosophers grab forks in a different order. This solves the deadlock problem.

Thread Throttling

A semaphore initialized to some maximum number of threads can throttle the number of threads that are ever concurrently in a dangerous region.

This is because a semaphore will begin waiting whenever we reach below 0, with sem_wait().

How to Implement Semaphores

Implementing zemaphores, compare to our pseudocode implementation here: ^a1d7a1

typedef struct __Zem_t {

int value;

pthread_cont_t cond;

pthread_mutex_t lock;

} Zem_t;

// only one thread can call this

void Zem_init(Zem_t *s, int value) {

s->value = value;

Cond_init(&s->cond);

Mutex_init(&s->lock);

}

void Zem_wait(Zem_t *s) {

Mutex_lock(&s->lock);

while (s->value <= 0)

// remember waiting for conditions with signals?

Cond_wait(&s->cond, &s->lock);

s->value--;

Mutex_unlock

}

void Zem_post(Zem_t *s) {

Mutex_lock(&s->lock);

s->value++;

Cond_signal(&s->cond);

Mutex_unlock(&s->lock);

}Common Concurrency Problems

Non-deadlock Bugs

There are two types of major non-deadlock bugs: atomicity violation and order violation.

Atomicity Violation

Thread 1::

if (thd->proc_info) {

fputs(thd->proc_info, ...); // not protected

}

Thread 2::

thd->proc_info = NULL; // also not protectedWhen these two threads access the field proc_info, the non-null check in Thread 1 could be interrupted by Thread 2’s nullification. We must not make an atomicity assumption about the check for non-NULL of proc_info and the usage of proc_info in the fputs() call.

We can put a lock around both executions to prevent this bug.

Order-Violation Bugs

Thread 1::

void init() {

// code assumes that mThread is created...

mThread = PR_CreateThread(mMain, ...);

}

Thread 2::

void mMain(...) {

mState = mThread->State;

}Order violation: the desired order between two memory accesses is flipped.

How do fix this?

pthread_mutex_t mtLock = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

pthread_cond_t mtCond = PTHREAD_COND_INITIALIZER;

int mtInit = 0;

Thread 1::

void init() {

...

mThread = PR_CreateThread(mMain, ...);

// signal that the thread has been created...

pthread_mutex_lock(&mtLock);

mtInit = 1;

pthread_cond_signal(&mtCond);

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mtLock);

}

Thread 2::

void mMain(...) {

...

// wait for the thread to be initialized...

pthread_mutex_lock(&mtLock);

while (mtInit == 0)

pthread_cond_wait(&mtCond, &mtLock);

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mtLock);

mState = mThread->State;

...

}I don’t really get this for now, but moving on…

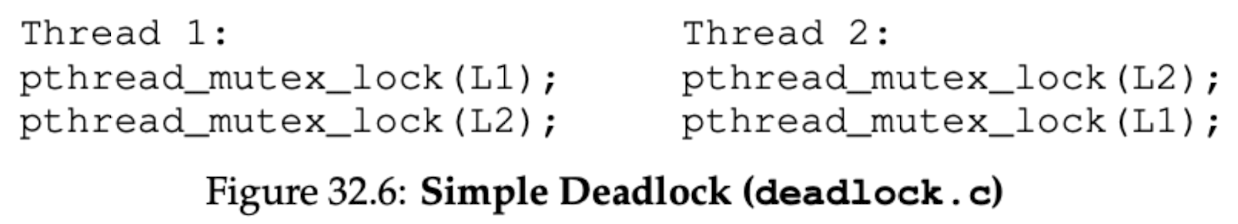

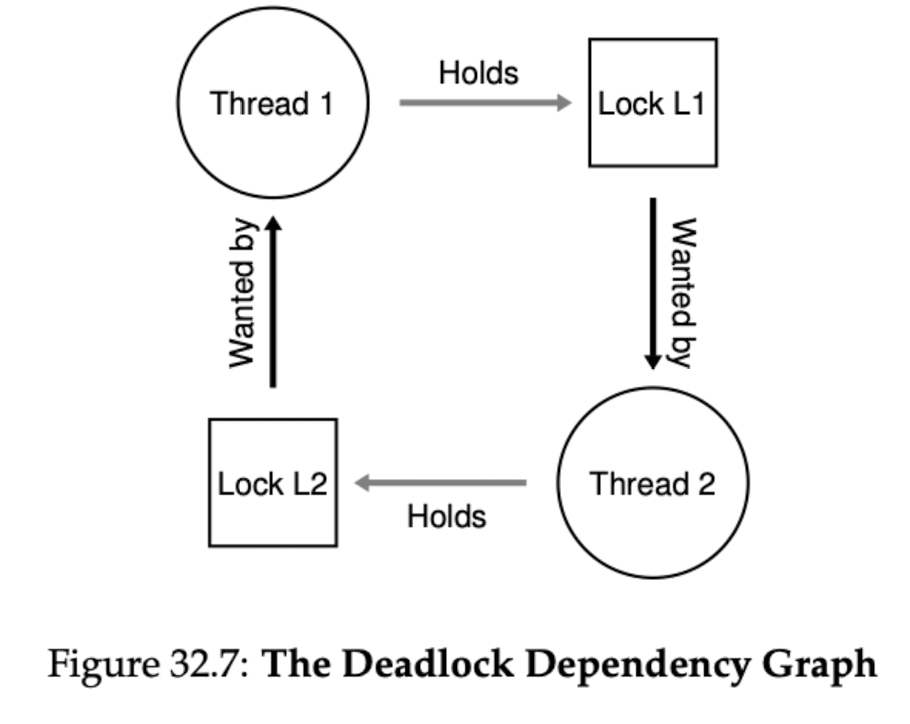

Deadlock Bugs

| Code | Dependency Graph |

|---|---|

|  |

It’s when everything gets locked and there is no way out!

- Why do deadlocks happen?

- Complex dependencies in large code bases

- Encapsulation: hidden implementations make software behavior harder to predict

- Conditions for Deadlock (any not met, deadlock can occur):

- Mutual Exclusion: Threads claim exclusive control of resources they require

- Hold-and-wait: Threads hold resources allocated to them while waiting for additional resources (some additional lock they want to acquire)

- No preemption: Resources (e.g., locks) cannot be removed by force from threads that are holding them

- Circular wait: There exists a circular chain of threads such that each thread holds one or more resources that are being requested by the next thread in the chain

Solutions for deadlock conditions

Circular wait

- total ordering: always order threads to acquire locks one-by-one

- partial ordering: pre-defined orders for program to follow

Hold-and-wait

- Call some global lock for acquiring multiple locks, and then unlock the global lock once done

- issue: encapsulation works against us, and concurrency decreases as locks are acquired early.

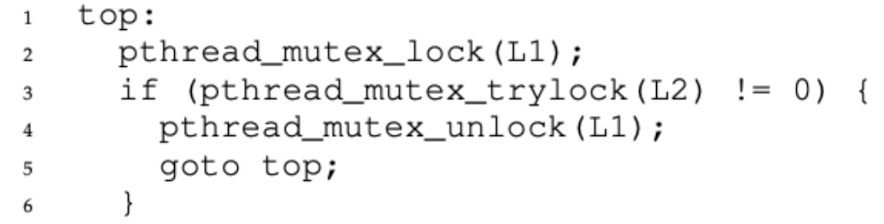

No Preemption

- There are more flexible locks available:

pthread_mutex_trylock(): grab the lock if it is available and return success, or return error code indicating lock is held

- but a livelock can happen with this method, where two threads continuously avoid each other in grabbing the potential deadlock in question…

Mutual Exclusion

There are methods of lock-free systems, where we make more atomic functions:

void AtomicIncrement(int *value, int amount) {

do {

int old = *value;

} while (CompareAndSwap(value, old, old + amount) == 0);

}

void insert(int value) {

node_t *n = malloc(sizeof(node_t));

assert(n != NULL);

n->value = value;

do {

n->next = head; // critical section handled by CompareAndSwap

} while (CompareAndSwap(&head, n->next, n) == 0); //

}The code here updates the next pointer to point to the current head, and then tries to swap the newly-created node into position as the new head of the list. However, this will fail if some other thread successfully swapped in a new head in the meanwhile, causing this thread to retry again with the new head.

Deadlock Avoidance (via Scheduling)

If we know when locks will be grabbed, then we can schedule them one by one globally to avoid deadlocks.