The Process

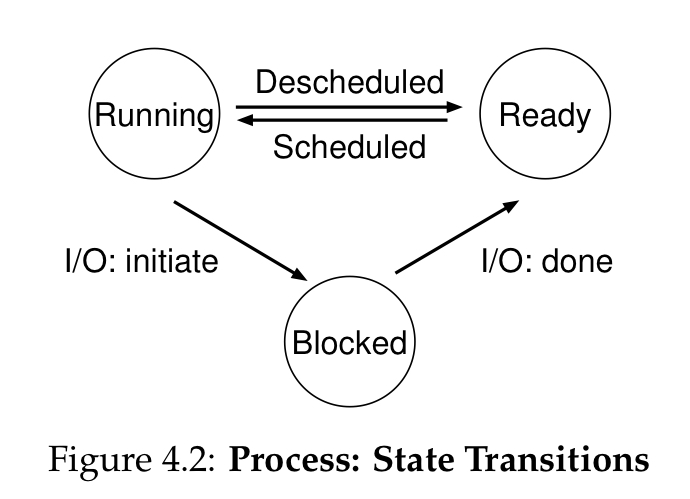

Process states

- READY: when ready to run but another process is running

- RUNNING: process is running on processor

- BLOCKED: when used to run but is blocked by some process (usually IO)

These states are stored in a Process Control Block (PCB), which are organized in a process list.

Process API

Each process has an API that can create, destruct, and make other useful calls.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("hello world (pid:%d)\n", (int) getpid());

int rc = fork();

if (rc < 0) { // fork failed

fprintf(stderr, "fork failed\n");

exit(1);

} else if (rc == 0) { // fork successful, run child process

printf("hello, I am child (pid:%d)\n", (int) getpid());

} else {

printf("hello, I am parent of %d (pid:%d)\n",

rc, (int) getpid());

}

return 0

}prompt> ./p1

hello world (pid: 29146)

hello, I am parent of 29147 (pid: 29146)

hello, I am child (pid: 29147)

prompt>- When

fork()is called, process creates child copy of itself, but- returns PID of child for parent

- and returns 0 for child

- meaning parent is allowed to manage and monitor the child process with

wait()andwaitpid()calls

- And strangely, code runs in child process only after the

fork()call - The

exec()family allows child to break free from its similarity to its parent and execute an entirely new program- so calling

exec()to a whole new executable in a child process allows parent process to run different programs in one program

- so calling

- Process control is available in the form of signals

SIGINT(interrupt),SIGTSTP(stop)

Limited Direct Execution

User to kernel workflow

- User calls system call

- Program executes trap instruction, which

- jumps into kernel and raises privilege to kernel mode

- and does privileged operations (I/O requests, executing OS instructions)

- when done, OS calls return-from-trap instruction

- Program executes trap instruction, which

- Returns back to user-mode, decrease privilege level

Details

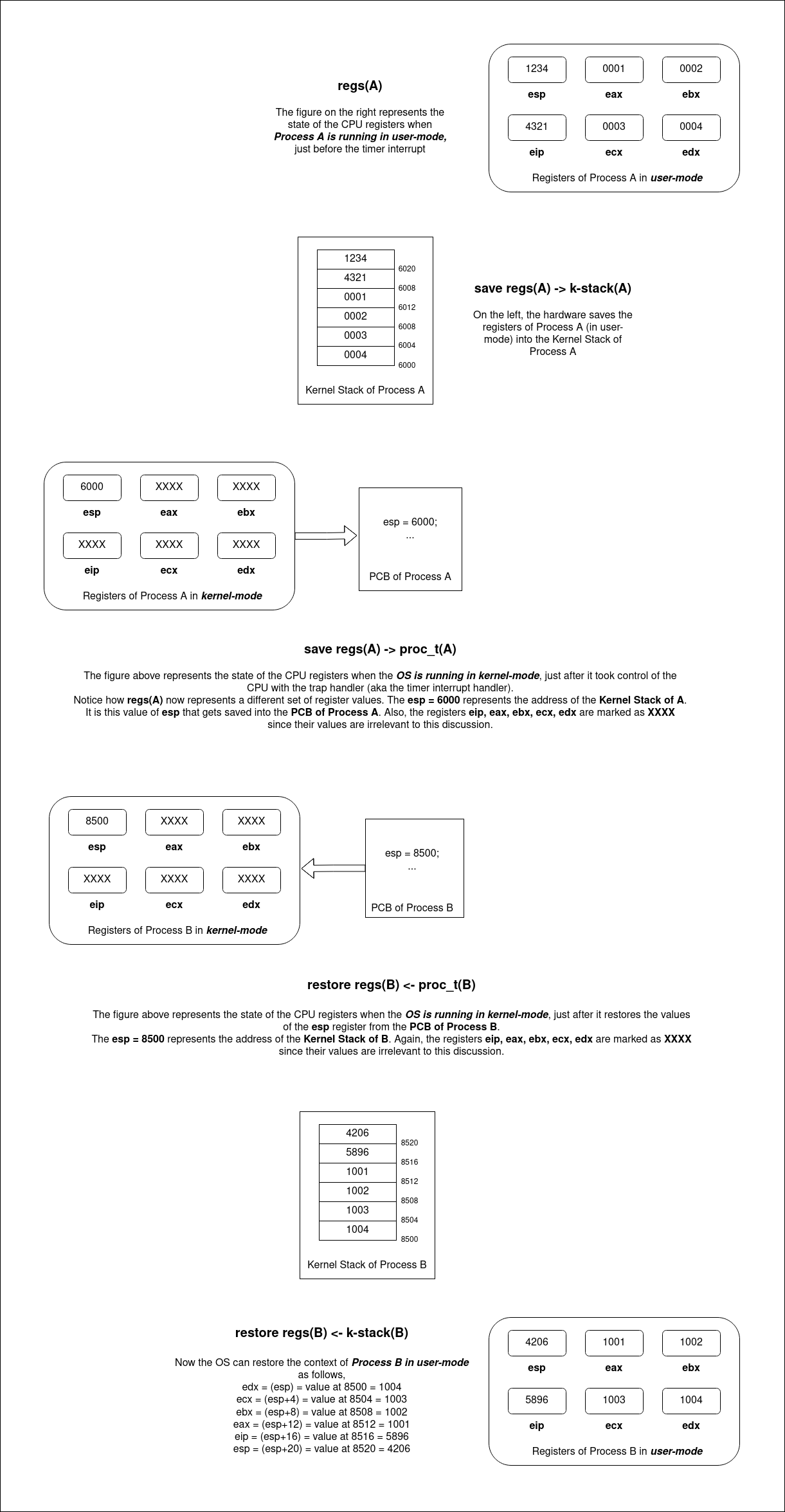

- When executing a trap, x86 pushes program counter, flags, and other registers onto a per-process kernel stack

- And return-from-trap pops these values off the stack and resumes execution

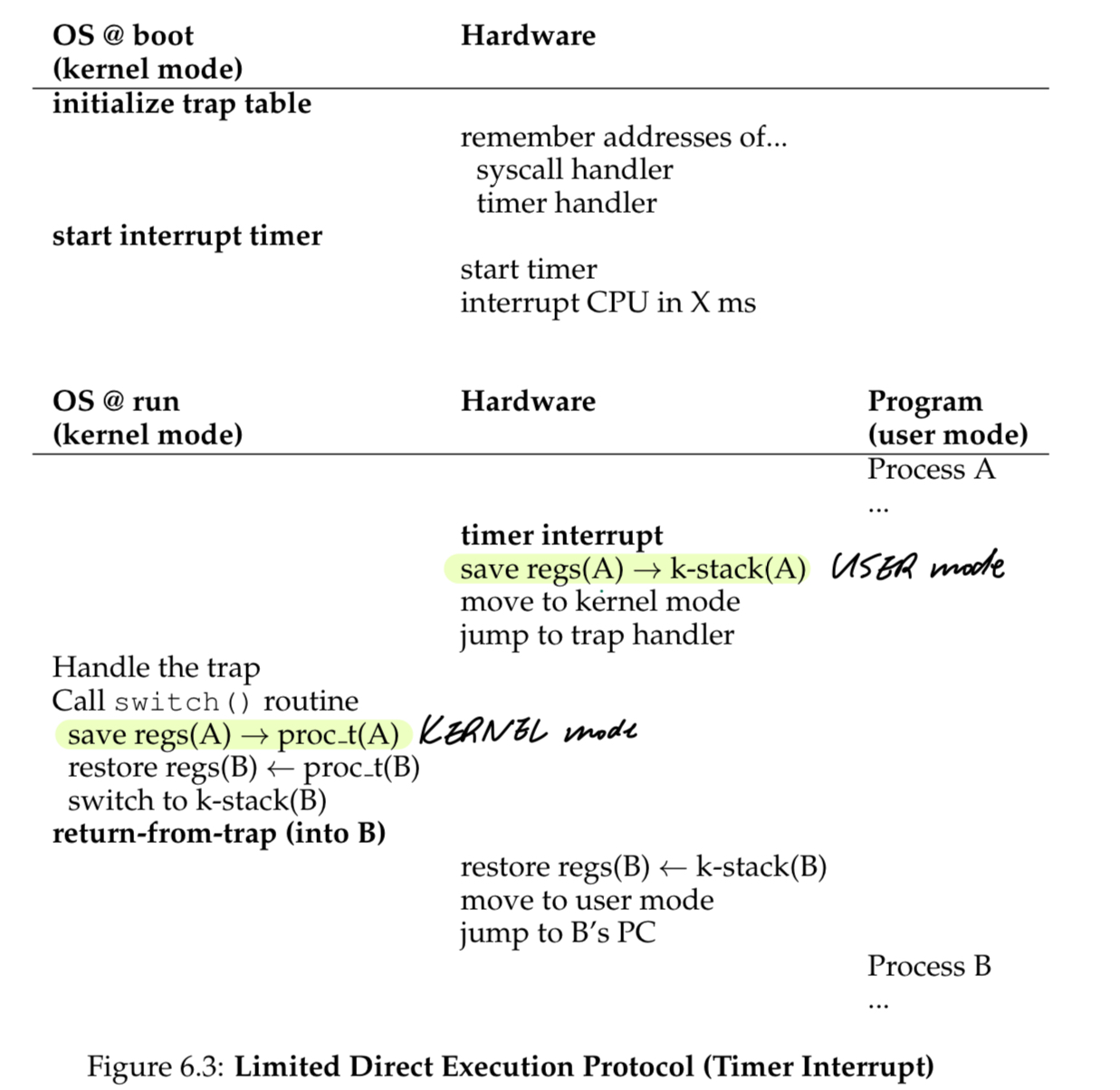

Timer interrupt implementation

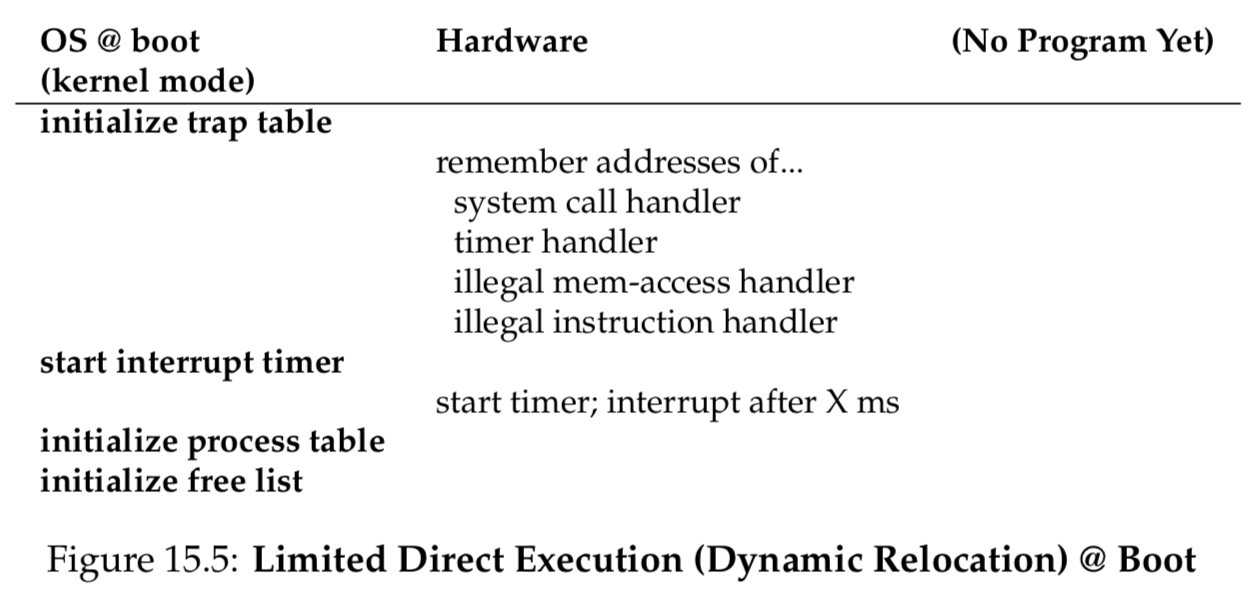

- Kernel sets up a trap table at boot time, which tells the hardware locations of trap handlers

- Kernel then sets up timer

- trap handlers specify what code to run when exceptional events occur

- i.e., keyboard interrupt, system call, etc.

- to specify each system call, we assign a system-call number to each system call

- user code should know the system call number it desires to call

- OS does a check on this number

- context switch: OS saves a few register values (general purpose registers, PC, kernel stack pointer of currently-running process, switch to the kernel stack for the soon-to-be executing process) for currently-executing process, and restore a few for the soon-to-be-executing process

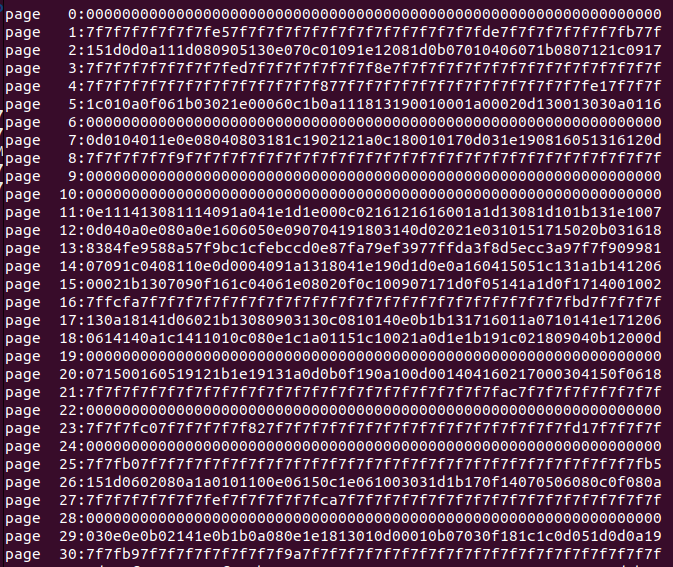

How to think about proc.t(A) and k-stack(A)

- Kernel Stack: the kernel stack is used to store the state of a process during a context switch. This includes the CPU registers that the process is currently using. When an interrupt occurs, the state of the process needs to be saved quickly so that CPU can handle the interrupt. By saving the state onto the kernel stack, the operating system ensures that it has all the information to resume the process later. The kernel stack is also used because it is a safe area of memory that user processes cannot access, protecting the saved state from accidental corruption.

- Process Table: the process table entry holds the longer-term state of the process, including register values, when the process is not currently executing. This saved state is used when the process is scheduled to run again after being preempted by another process. Saving the state in the process table is essential for the operating system’s scheduler, which might not schedule the process to run again immediately after the interrupt is handled.

- Key points:

- The CPU uses the process table to take care of scheduling, since process control blocks contain more information about the process than just the registers.

- The process table also is a global data structure, holding static information about all processes in the system including those not currently running.

- Also keep in mind that storing information in the process table is not exclusively done in an interrupt, it also occurs when the process begins and terminates.

- The kernel is a transient storage; it only holds data while a process is in the kernel mode and needs to be quickly accessible to save and restore state.

Scheduling

Design scheduling policy:

- interactive programs: user-facing programs that need to feel responsive

- batch programs: programs running long-running background tasks

Metrics to optimize type of performance

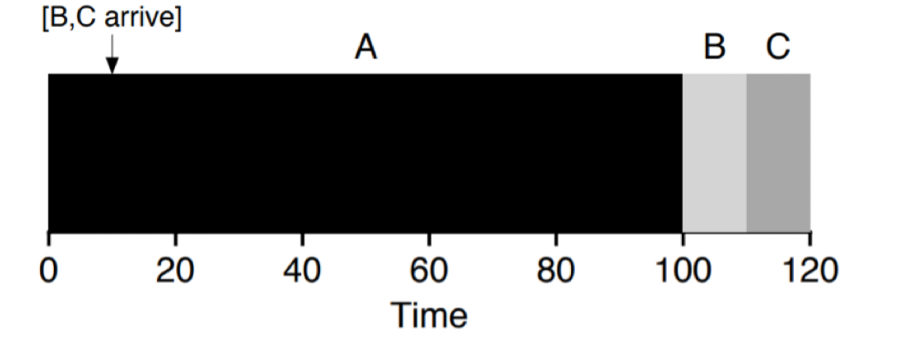

- turnaround time (STCF optimal)

- $T_{\text{turnaround}} = T_{\text{completion}} - T_{\text{arrival}}$

- i.e., how long do tasks take from arrival to completion?

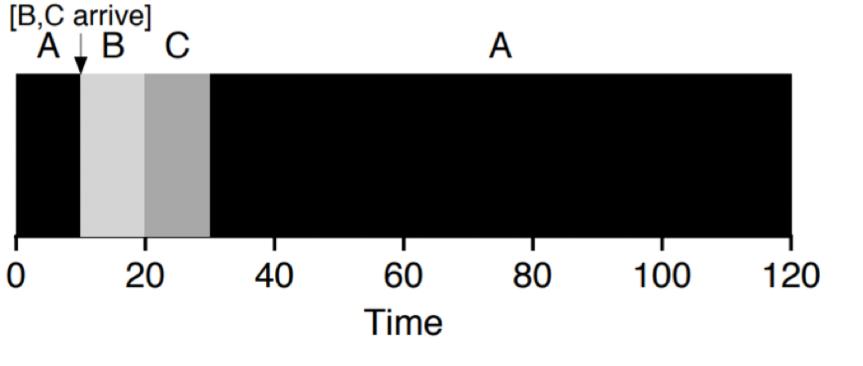

- response time (RR optimal)

- $T_{\text{response}} = T_{\text{firstrun}} - T_{\text{arrival}}$

- i.e., how long do tasks take from getting first run since arrival?

Scheduler Types and Issues

- FIFO/FCFS

- Whichever job arrives first gets run first.

- Turnaround time suffers when short jobs must wait for long jobs.

- SJF

- Shortest job first.

- Does not account for late arrivals.

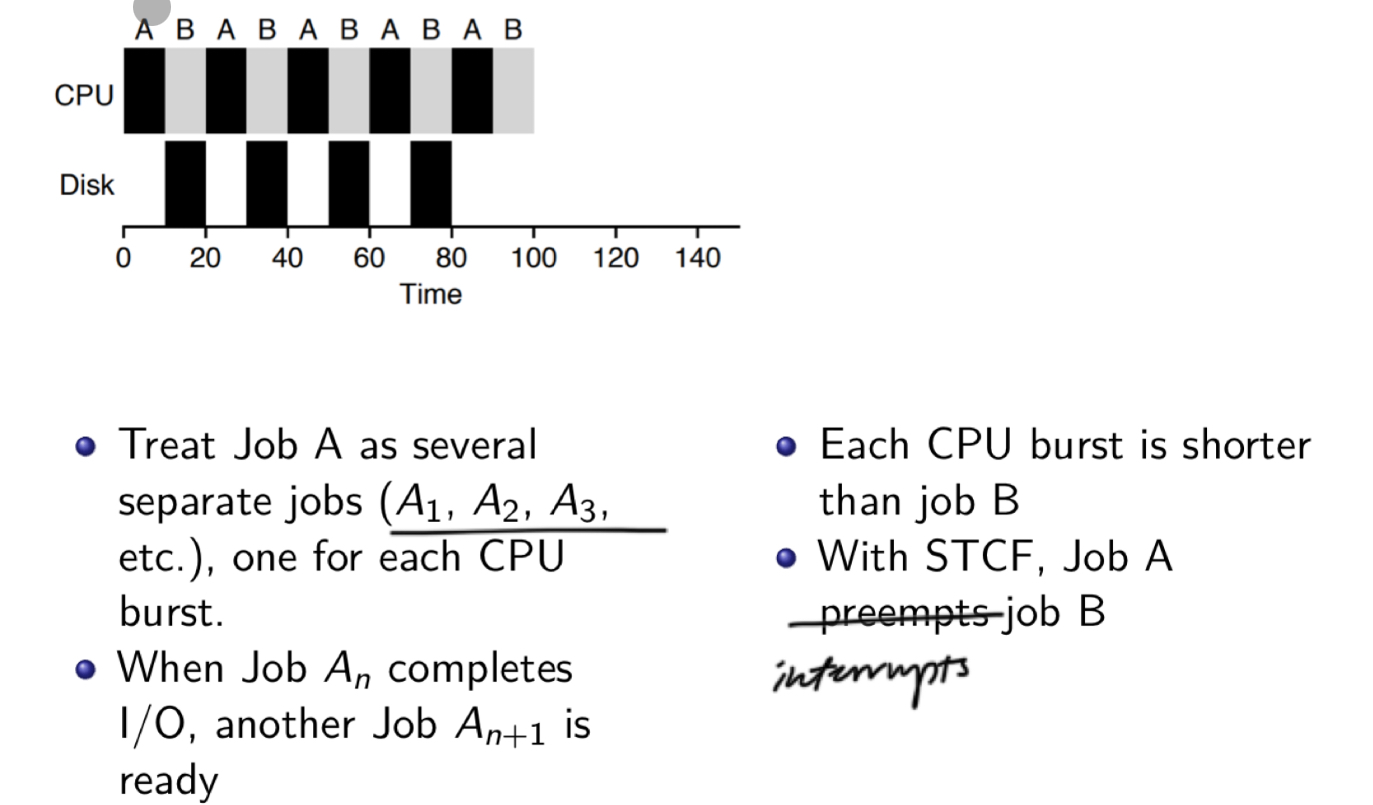

- STCF (optimal turnaround time)

- Shortest time-to-completion first

- preemptive, meaning schedule different job by taking CPU away from running job

- synonymous to interrupt

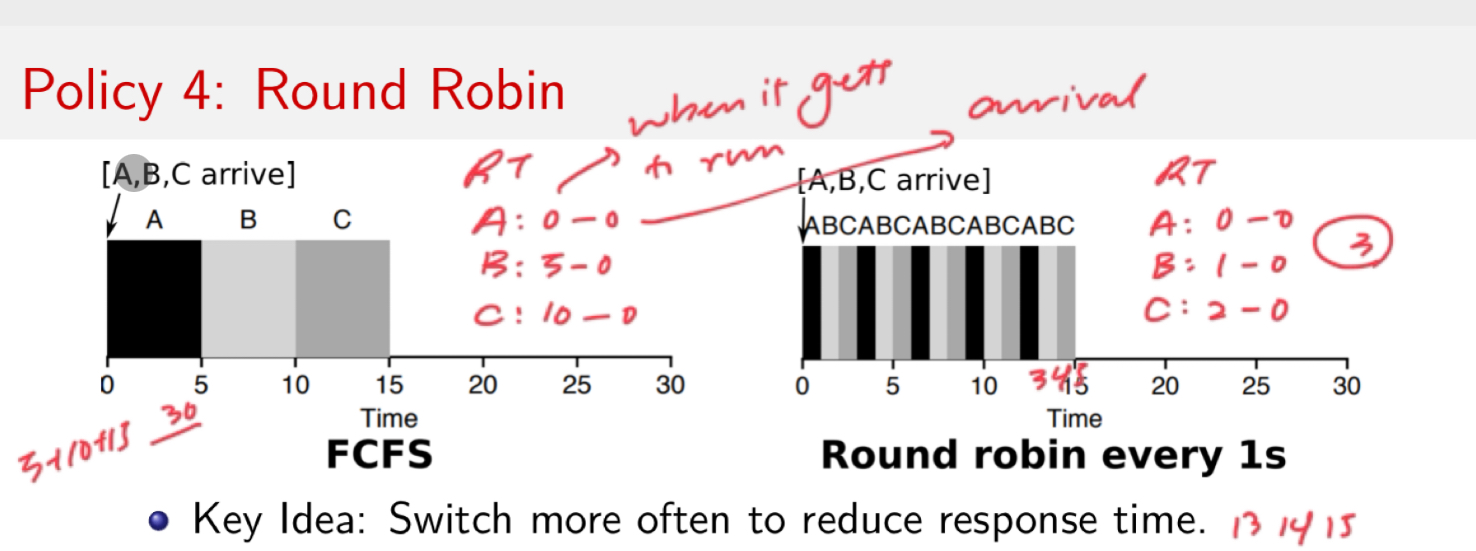

- RR (optimal response time)

- Switch more often to reduce response time

- Challenges:

- What is a good time slice?

- What is the overhead of a context switch?

- (each switch requires context saving)

- IO Aware Scheduling

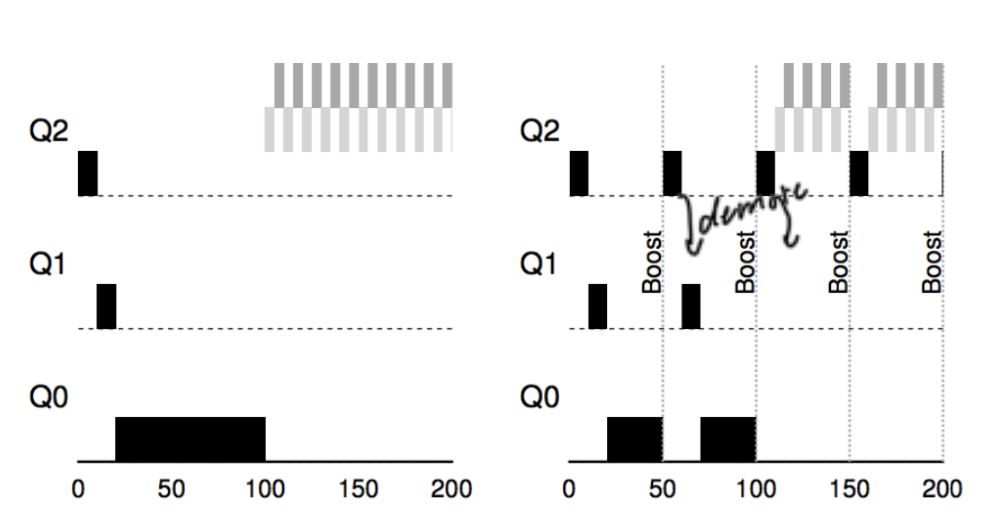

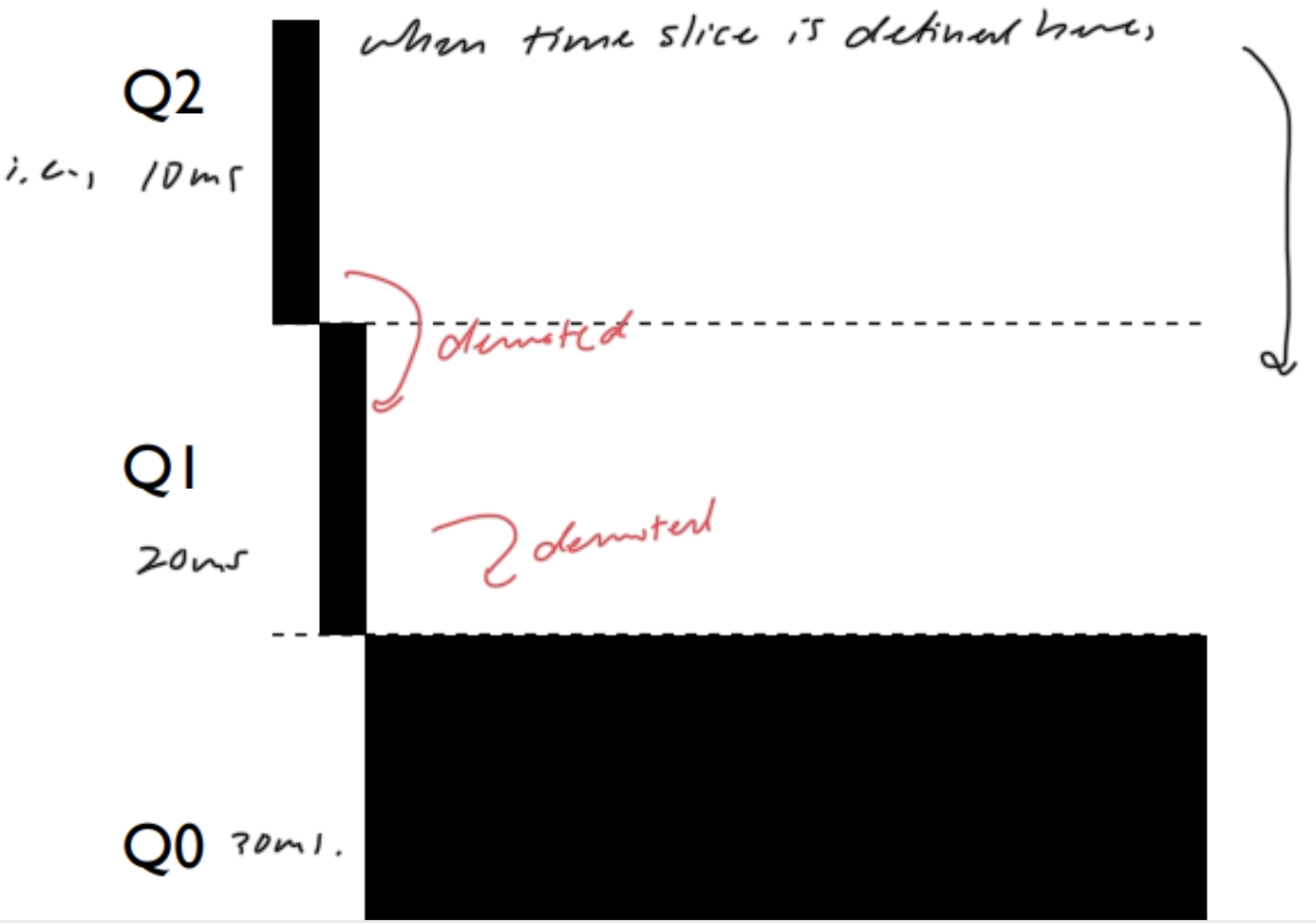

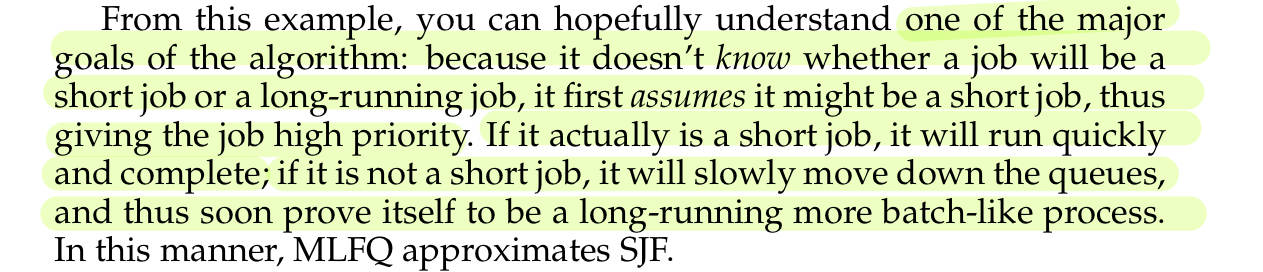

- MLFQ (optimal response/turnaround time)

- Rule:

- If $\text{Priority}(A) > \text{Priority}(B)$, then $A$ runs.

- If $\text{Priority}(A) == \text{Priority}(B)$, then $A$ and $B$ run in RR (ensures responsiveness) using the time slice of the given queue

- All jobs start at top priority

- If job uses whole time slice, demote process (longer time slices at lower priorities)

- Once a job uses up its time allotment at a given level regardless of how many times it has given up the CPU, its priority is reduced.

- After some time period $S$, move all jobs to the topmost queue.

- Rule:

Memory Virtualization

Address Spaces

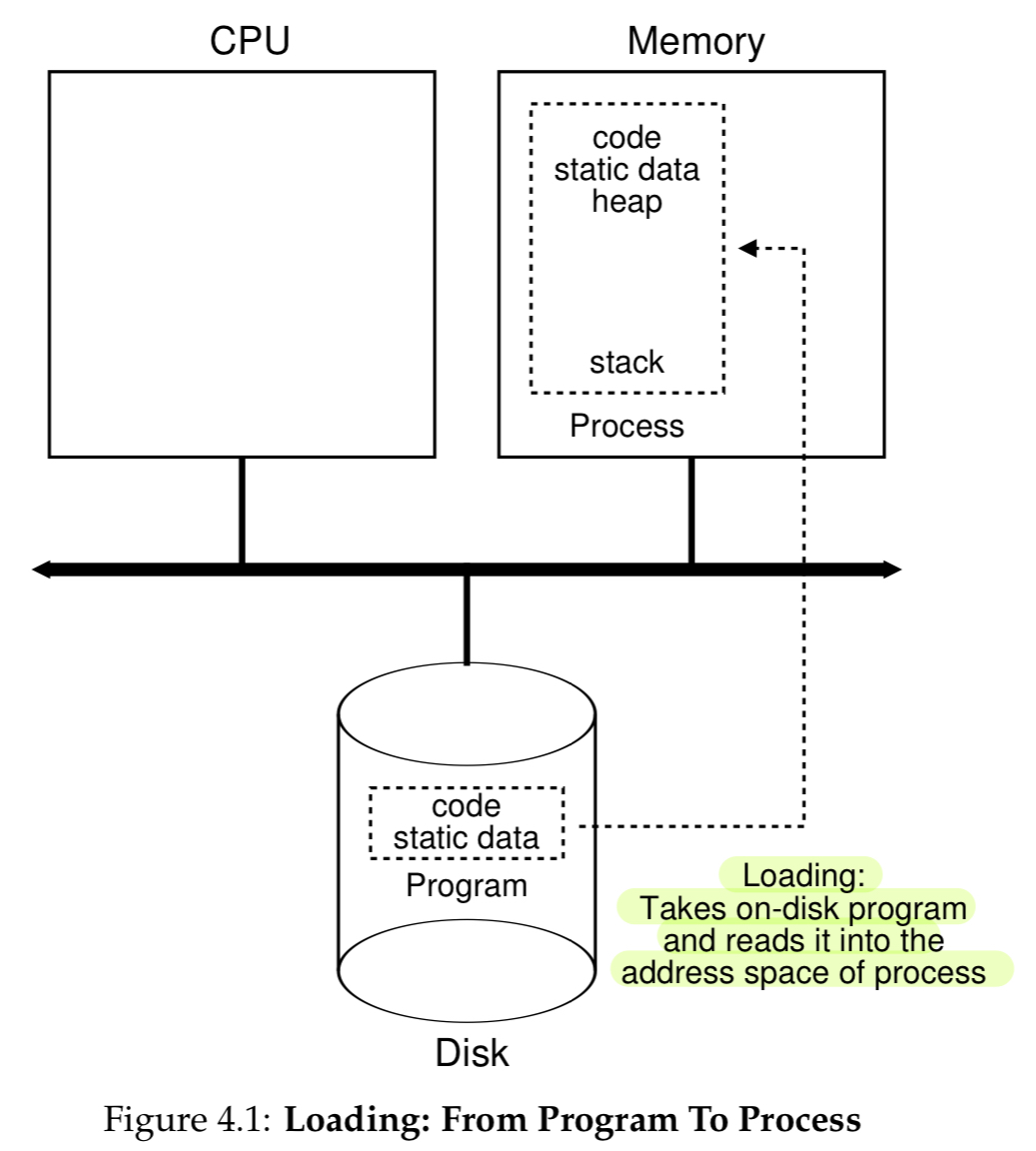

Process: running program

- Load code (usually executable format) from disk into memory

- OS allocates space in memory for stack, where local variables, function parameters, and return addresses are stored

- OS allocates space for heap, where dynamically allocated data is stored

- OS initializes file descriptors

- Standard input

- Standard output

- Error

- Jump to

main(), and transfer control of CPU to newly-created process

Address space: memory that the process can address, physical memory abstracted in an easy-to-use form

OS must build an abstraction of a private, potentially large address space for multiple running processes on top of a single physical memory. We do this by virtual memory.

Virtual memory goals:

- Transparency: invisible to the running program, giving a “transparent” lens to the actual, physical memory

- Efficiency: make virtualization as efficient as possible in time and space.

- Protection: make sure to protect process from one another and the OS

Memory API

Declaring memory on the stack in C:

void func() {

int x; // declares an integer on the stack

// ...

}Declaring memory on the heap in C:

void func() {

int *x = (int *) malloc(sizeof(int));

// first stores *x on the stack

// then points *x to allocated space in heap

}(int *) is used to cast the void * return value of malloc, but is not necessary as C automatically casts void pointers to the appropriate type.

Common Errors:

- Forgetting to allocate memory

- Not allocating enough memory

- Forgetting to initialize memory (forgetting to fill in some values to newly-allocated data type)

- Forgetting to free memory

- Freeing memory before you’re done with it

- Double-freeing

- Calling

free()incorrectly

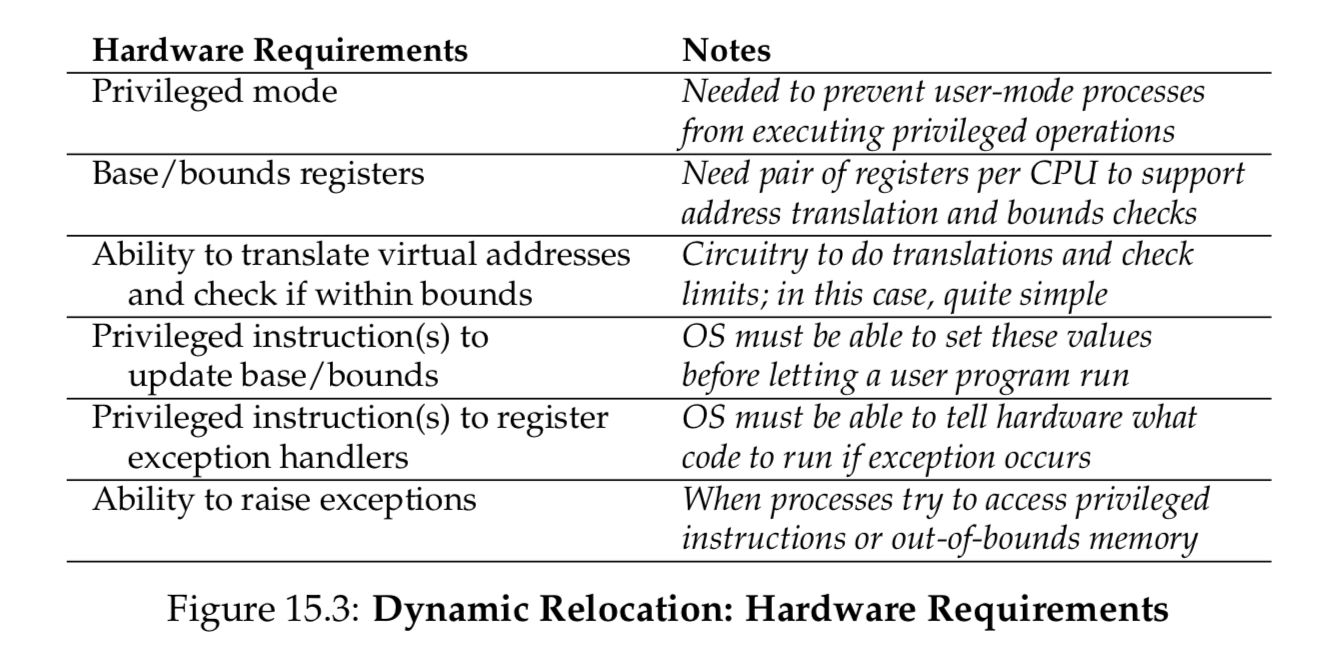

Address Translation (Base + bounds)

Goal: we want to efficiently and flexibly virtualize memory.

address translation: hardware translation from virtual to physical memory

dynamic relocation or base and bounds: base register stores the base of where virtual memory actually resides in physical memory, and bounds is the size of the space the virtual memory takes up in physical memory : physical address = virtual address + base

- base register is decided by OS at the beginning of a program

- bounds register is also initialized at process creation, and checks whether a memory reference is within bounds

- obviously, bounds register is therefore size of the process

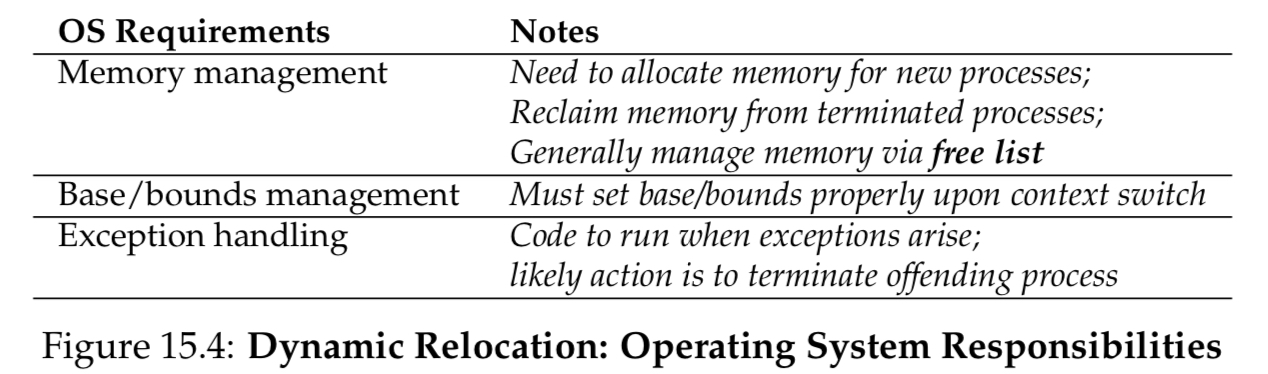

Responsibilities!

base and bounds are saved and restored at the PCB!

Base and bounds is not perfect!

It leads to internal fragmentation, where space allocated for stack and heap are just wasted. This leads us to the first attempt to make better use of memory, segmentation.

Segmentation

segmentation: have a base+bounds pair per logical segment of the address space

a little bit of mental gymnastics in calculating base+bounds:

- When we get a memory access to the heap,

- Check offset to heap from virtual address, then subtract offset from address of memory access

- Then add subtracted value to physical heap address offset

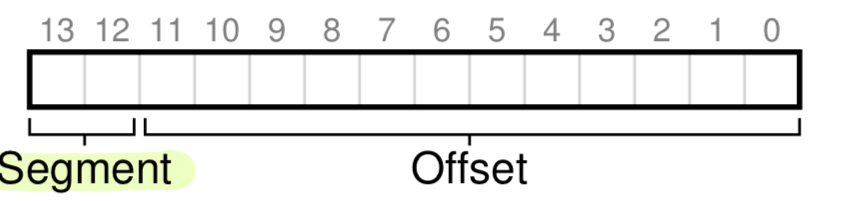

Explicit approach

to not have to do the mental gymnastics:

for a 14-bit virtual address, we can use the top two bits to denote:

00for code01for heap10for stack

and the last 12 bits for the offset.

For example, the virtual address 4200 is, in binary, 01 0000 0110 1000.

This means we are trying to access the heap, with offset 104.

We can perform the bounds check by seeing whether offset is less than the bounds.

but since we are chopping off the last two bits, the address space gets reduced from 16KB to 4KB.

implicit approach fixes this issue:

Implicit approach

Hardware determines the segment by noticing how the address was formed.

- For example, if the address was generated from the program counter, then it is an instruction fetch within the code segment

- if the address is based off the stack or base pointer, it must be in the stack segment

- any other address must be in the heap.

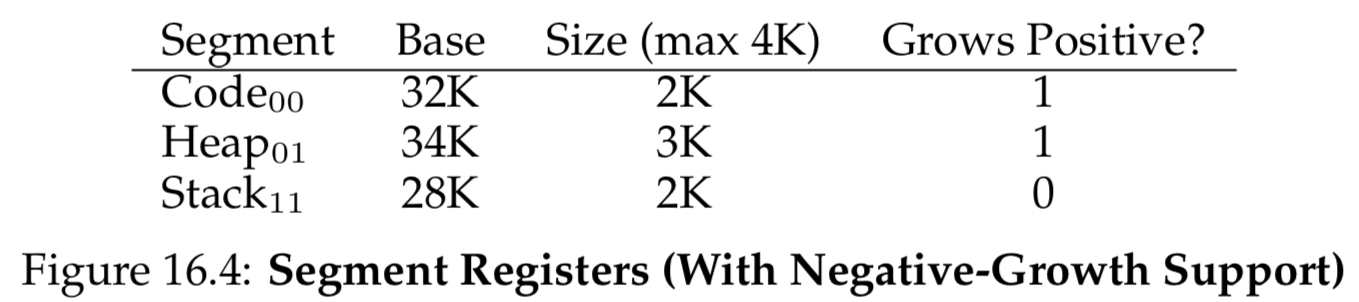

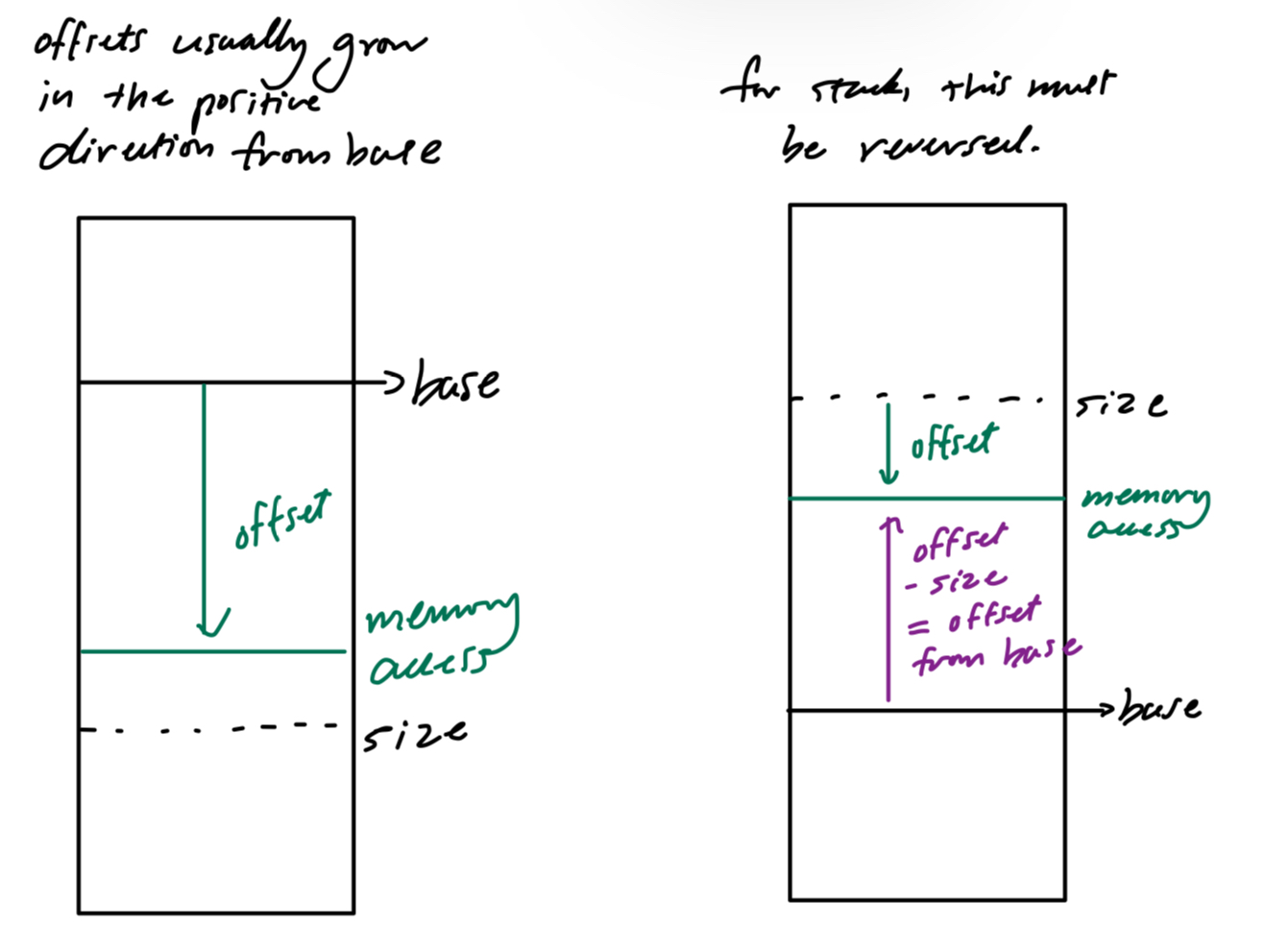

Negative growth for stack

Unlike the heap, the stack grows negatively. We need hardware support for this:

Virtual address accessing stack: 11 1100 0000 0000 (hex 0x3C00)

Segment: stack; Offset: 3KB

So for the given example, we do offset - maximum size which is 3K - 4K = -1K, and add the resulting value to the base, so 28K - 1K = 27K.

We can do a bounds check by ensuring that the absolute value of the negative offset is less than or equal to the segment’s current size.

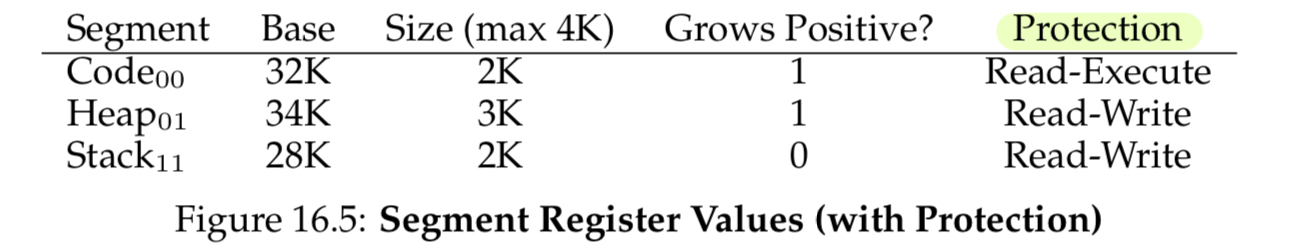

Protection bits

Making the code segment read-execute allows other programs to share code. The protection bit facilitates this. We could add a check after bounds check to make sure that a user process is not accessing protected memory.

Fine-graned vs. coarse-grained segmentation

coarse-grained: chop up address space into large chunks (code, stack, heap)

fine-grained: chop up address space into even finer chunks, which requires segment tables to keep track of all segments from hardware

Issues and solutions of segmentation

OS needs to context switches

Just store the segment registers and restore them.

Heap sometimes needs to increase its size

In the case that the heap segment itself needs to grow, the memory-allocation library will perform a system call to grow the heap.

When this happens, the OS must provide more space, and update the segment size register to the new bigger size.

OS can reject when there is no space in memory.

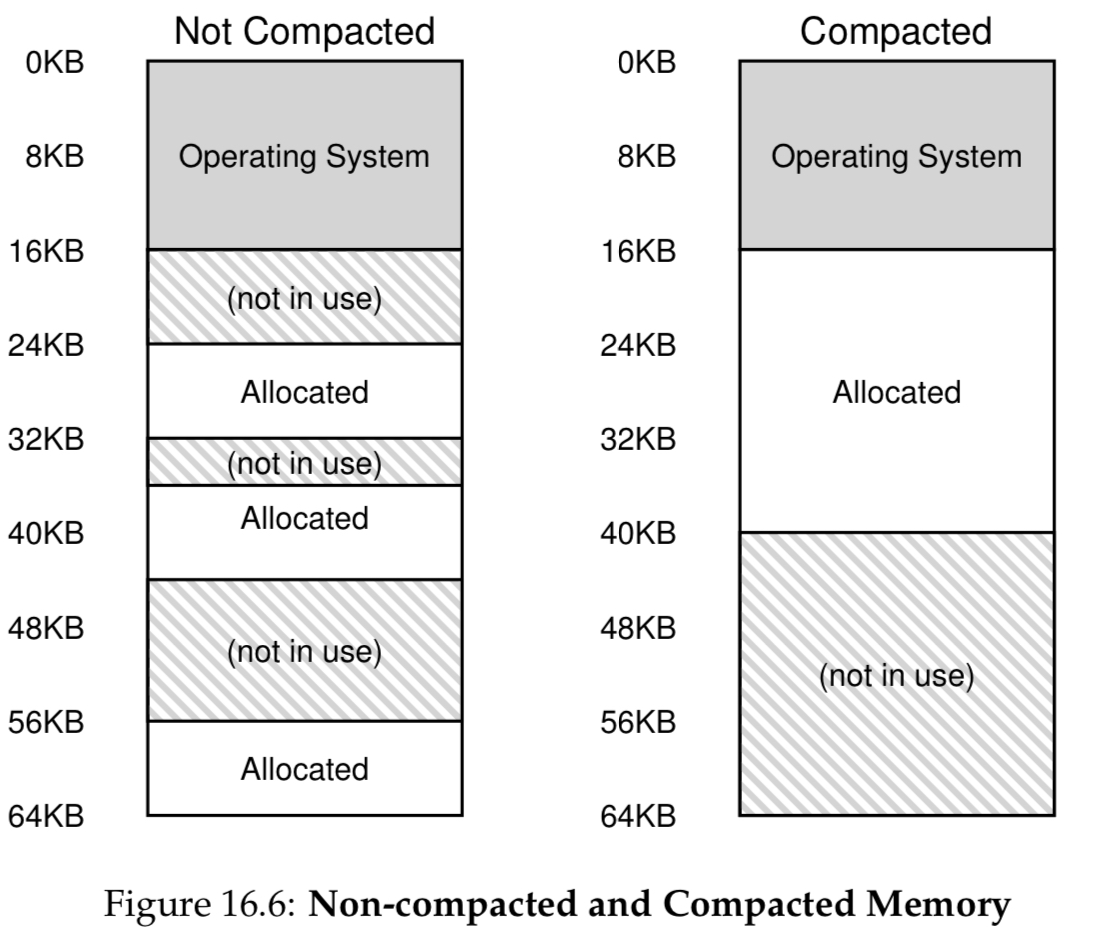

External Fragmentation

External fragmentation (left) happens when we create little holes of free space, making it difficult to allocate new segments.

Compaction is an option, but it is too computationally expensive.

We could also keep a free-list.

But the best solution is fixed-size chunks, or pages.

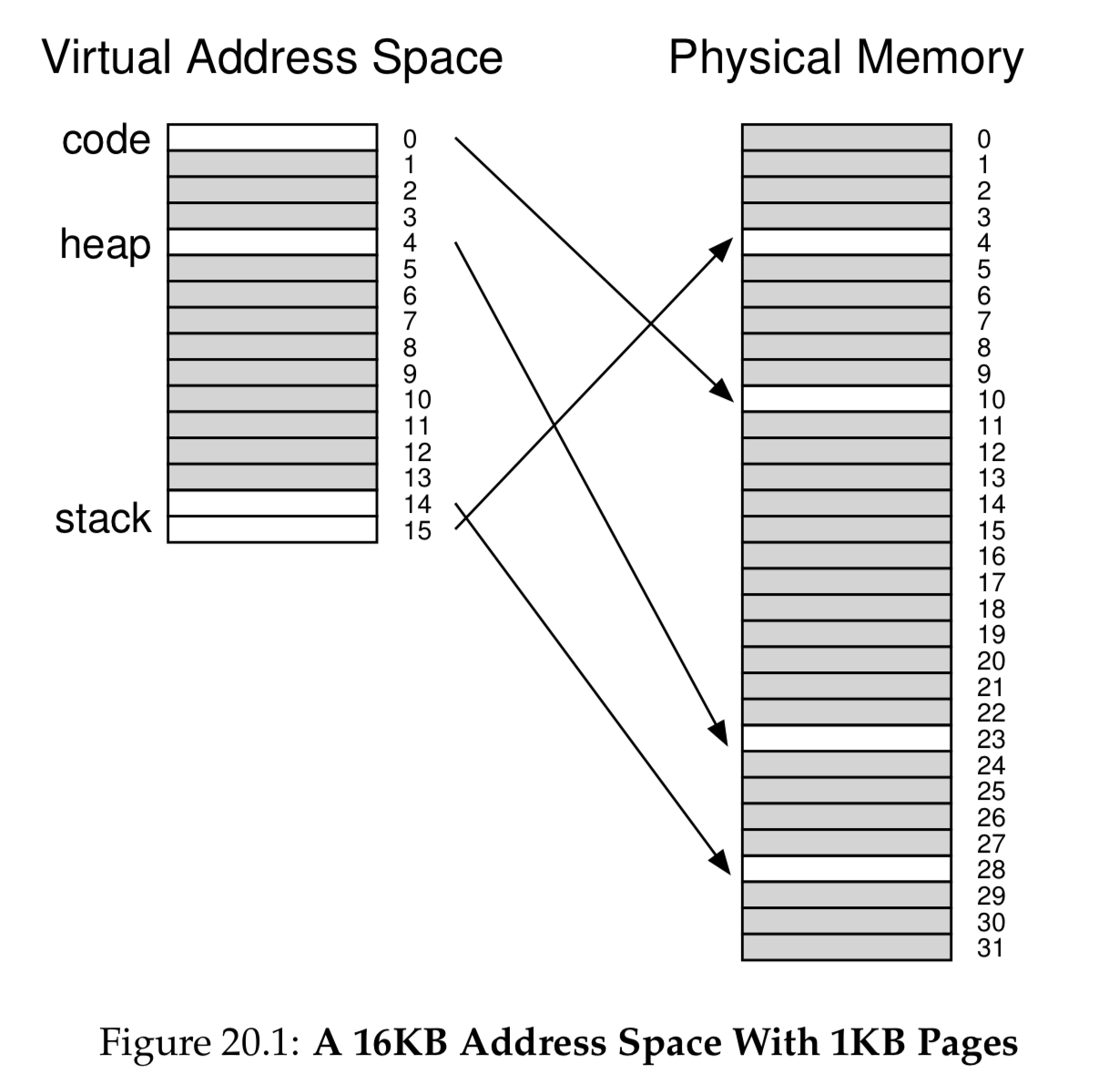

Paging

Instead of variable-sized segments (code, heap, stack), we will divide process’s address space into fixed-size units called pages. Correspondingly, we view physical memory as an array of fixed-sized slots called page frames.

The page table is a per-process data structure of the OS, where address translations are recorded. The page table is per-process because each process’s virtual memory maps to different physical addresses.

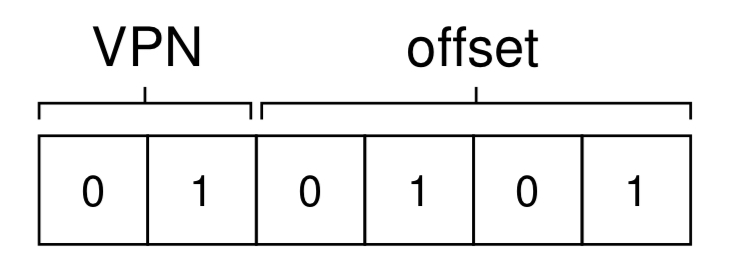

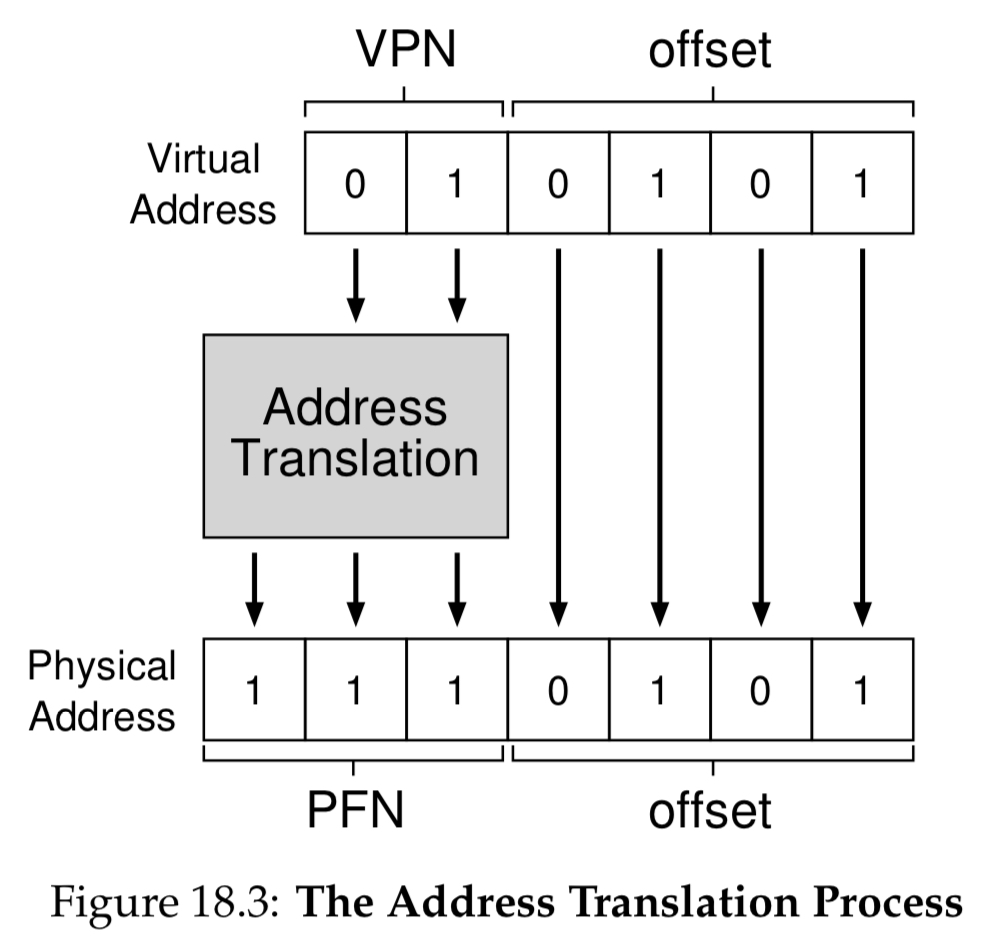

Translation

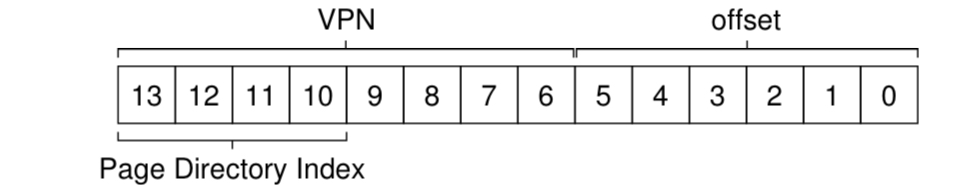

To translate a virtual address, we have to first split it into two components: the virtual page number (VPN), and the offset within the page.

For example, in a 64 byte ($64=2^6$) address space, with a page size of 16 bytes ($16 = 2^4$):

We dedicate 4 bits for the offset to fully traverse a page, and $64/16=4$ pages to select, which we can do with 2 bits for the VPN.

When we translate the address, we get virtual page 01 = 1, which we use to look up the physical frame. This gives us the physical frame number, which then generates the final physical address:

As you can see, we simply replace the virtual page number with the page frame number.

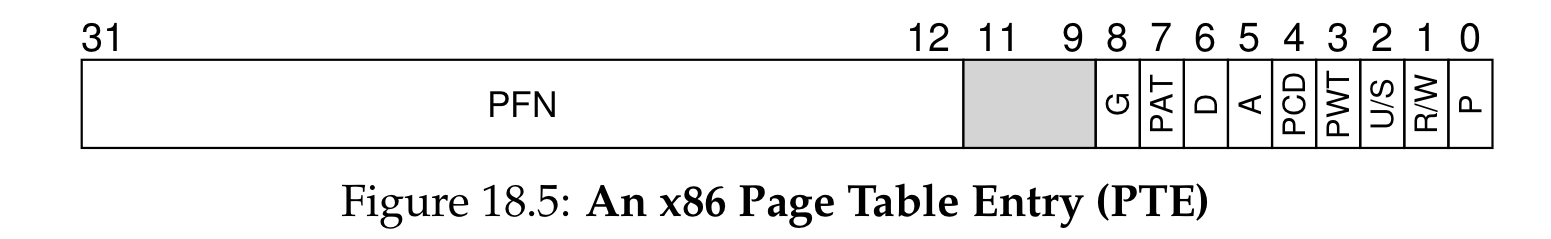

Page Table

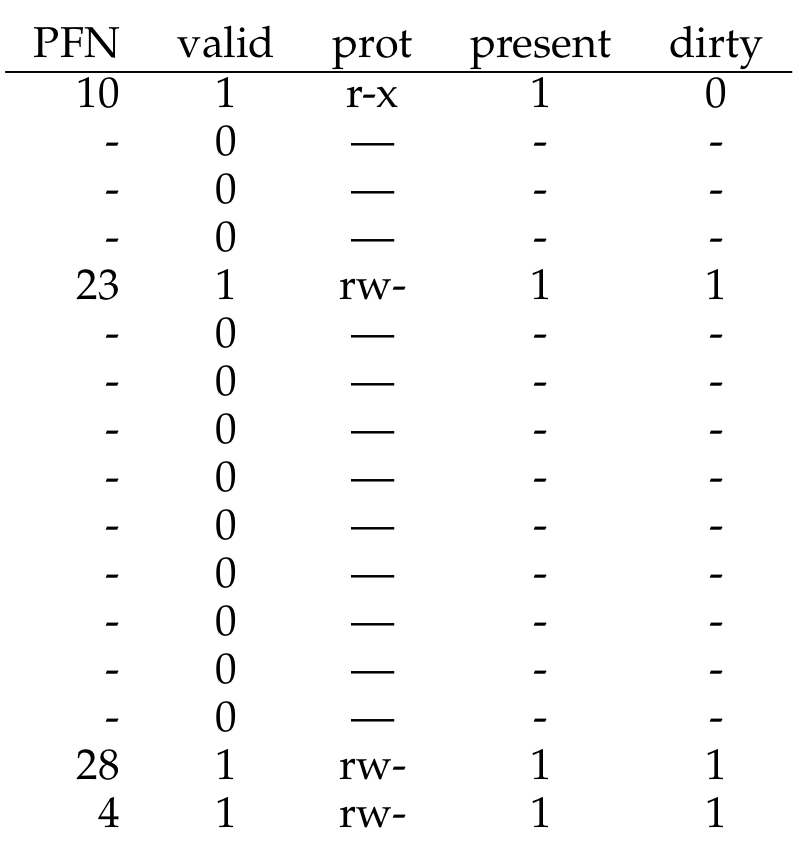

A page table entry looks like this:

The index of each entry allows the VPN to find the PFN.

Remember: VPN → PTE → PFN!

Accessing memory with paging, and issues

// extract the VPN from the virtual address

VPN = (VirtualAddress & VPN_mask) >> SHIFT

// for the address of the page-table entry (PTC)

PTEAddr = PTBR + (VPN * sizeof(PTE)) // PTBR is the page table base register

// fetch the PTE

PTE = AccessMemory(PTEAddr) // access 1

// check if process can access the page

if (PTE.Valid == False)

RaiseException(SEGMENTATION_FAULT)

else if (CanAccess(PTE.ProtectBits) == False)

RaiseException(PROTECTION_FAULT)

else

offset = VirtualAddress & OFFSET_MASK

PhysAddr = (PTE.PFN << PFN_SHIFT) | offset

Register = AccessMemory(PhysAddr) // access 2- Page tables access the memory many times, slowing down system

- Page tables take up too much space

Let’s solve this! (hopefully fast…)

Paging: Faster Translations (TLBs)

We don’t want to be translating every memory access, why don’t we cache some things?

Translation-lookaside buffer (TLB) is a part of the chip’s memory-management unit (MMU), which caches popular virtual-to-physical address translations.

Now, upon each virtual memory reference, the hardware first checks TLB, and if not present, adds it to the TLB. This makes use of spatial locality and temporal locality to reduce page table lookups, which is slower than the cache (it’s in physical memory).

TLB Control Flow

- Extract VPN from virtual address

- Check if TLB holds the translation for this VPN

- If it does, we have a TLB hit

- extract the page frame number from the relevant TLB entry, concatenate to virtual address, and form physical address.

- If it does not, we have a TLB miss

- access the page table to find the translation

- if translation is valid and accessible, add it to the TLB

- retry the instruction, which will now be found in the TLB

- access the page table to find the translation

- If it does, we have a TLB hit

Handling a TLB miss

Modern architectures manage the TLB with software.

- TLB miss, hardware raises an exception, raises privilege level, jump to trap handler

- Trap will look up translation in page table, update TLB, and return from trap

- a little different from normal return-from-traps—we need to return to the instruction that called the trap, not the instruction after the call

The OS also handles large chains of TLB misses with miss handlers in physical memory, or reserve entries in the TLB for perma-valid translations, which are called wired translations.

TLB valid bit ≠ page table valid bit! PTE valid bit denotes whether page is allocated or not. TLB valid bit denotes whether TLB has a valid translation within it.

TLB Contents

Each TLB entry looks like the following:

VPN | PFN | other bits

TLBs are found using the VPN, and are fully associative, meaning they can be anywhere… the hardware does a search for the entire TLB to find a VPN match.

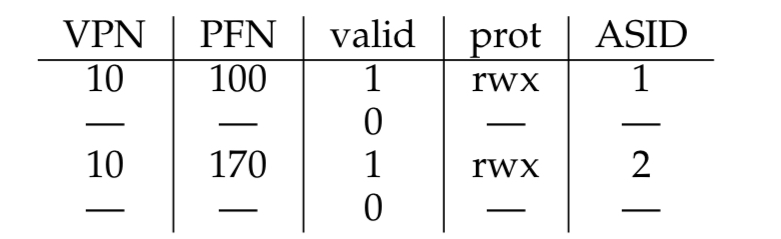

TLB Context Switches

Remember how pages are per-process? When switching from one process to another, we have to make sure that the about-to-be-run process doesn’t use translations from some previously run process.

We could flush everything (set all valid bits to 0), but this means we must incur TLB misses. So,

We use address space identifiers (ASID) instead, which is a field in the TLB that is similar to the PID. It keeps track of what process the TLB entry is meant for.

of course, hardware must now keep track of ASID per-process in a register.

TLB Replacement Policy

We want the policy to minimize the miss rate. Most common is LRU, where we evict the least recently used entry.

Another option is to randomly evict, which additionally avoids corner-case behaviors.

Paging: Smaller Tables

We don’t want page tables to consume too much memory, can we have smaller page tables?

Bigger Pages

Making pages bigger means we will have to organize less of them in the page table.

but again, this causes internal fragmentation within the page.

Hybrid: paging and segments

It keeps on getting more and more complex…

In this case, we have a lot of unused space within the page table, as we are using very small chunks of code, heap, and stack. So what if we had page tables for each segment?

We involve the MMU again, but we use the base not to point to the segment itself but to hold the physical address of the page table of that segment.

bloo blah, implementation…

Problem: we are still using segmentation! it isn’t as flexible as we want. it also causes external fragmentation, as page tables are now arbitrary size, and finding free space for them is more complicated…

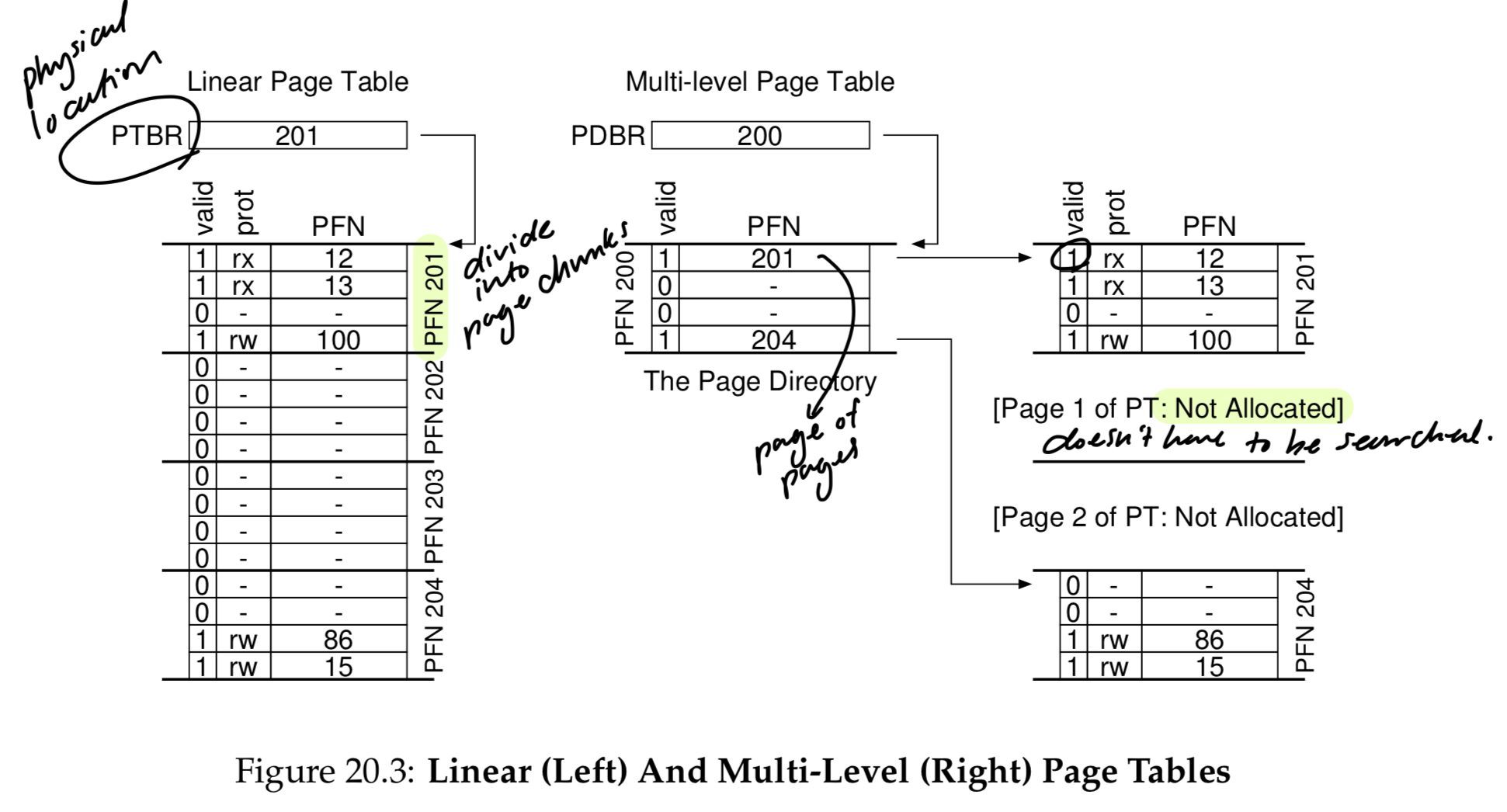

Multi-level Page Tables

Control Flow:

- Make page table into page-sized units

- if an entire page of page-table entries is invalid, don’t allocate that page of the page table at all.

- The page directory can be used to tel you where a page of the page table is…

Simply put, multi-level table makes parts of the linear page table disappear, and tracks which pages of the page table are allocated with the page directory.

If PDE is valid, then at least one PTE is valid.

If PDE is not valid, then rest of PDE is not defined.

remember: the goal is smaller page tables!

Another advantage is that each portion of the page table fits in a page, making it easier to grab the next free page when it needs to allocate or grow a page. This adds a level of indirection.

With this method however, there is a time-space tradeoff. For each TLB miss, we now need to do two loads from memory.

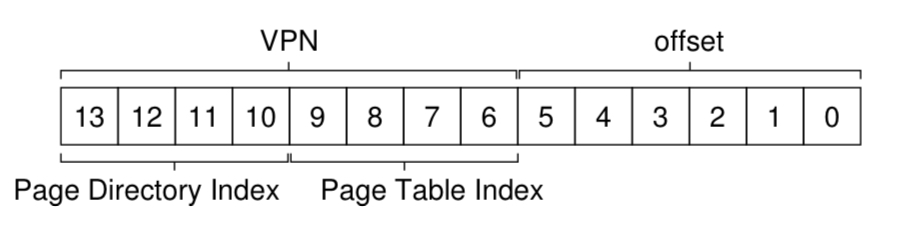

Logistics

Say we have a linear page table of $2^8=256$ entries.

Assuming each PTE is 4 bytes, our page table is 1KB ($256\times 4$ bytes) in size. Given that we have 64-byte pages, our 1KB page table can be divided into 16 ($1024/64=16$) 64-byte pages.

This means the page directory needs to have 16 entries ($=2^4$, 4 bits).

We now perform the following calculation: PDEAddr = PageDirBase + (PDIndex * sizeof(PDE)) (add the PDI to the PDBR to get PDE)

If PDE is invalid, we raise an exception.

If PDE is valid, we now get the PTI:

The PTI is calculated similarly:

PTEAddr = (PDE.PFN << SHIFT) + (PTIndex * sizeof(PTE))

Inverted Page Tables

Instead of having many PTs (one for every process), we keep a single table that has an entry for each physical page of the system.

Swapping

Some systems place page tables in kernel virtual memory, allowing the system to swap some of the tables to disk when memory pressure gets tight.

A practical example

Given virtual address needs 15 bits (5 for offset, 10 for VPN (5 for PDI and PTI))

Given virtual address 0x0214

binary : 0|000 00|10 000|1 0100

decimal: PDI:0 PTI:16 OFF:20

And given page directory base register (PDBR) 13

- Access page 13, then offset using PDI by byte (`sizeof(PDE))

- Retrieve

0x83, which translates to1|000 00111denotes valid bit, the rest is page number of page table000 0011$\rightarrow_{{decimal}}$3

- Access page 3, offset using PTI by byte (16)

- Retrieve

0x8e, which translates to1|000 1110000 1110is the page frame number- We now replace the VPN with PFN:

0001 1101 0100

- Final physical address is

0001 1101 0100, or in hex,0x1d4.